Late in the Jim Crow era, the island became a place for legendary Black acts to perform

By Jewel Wicker

Photos courtesy of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum

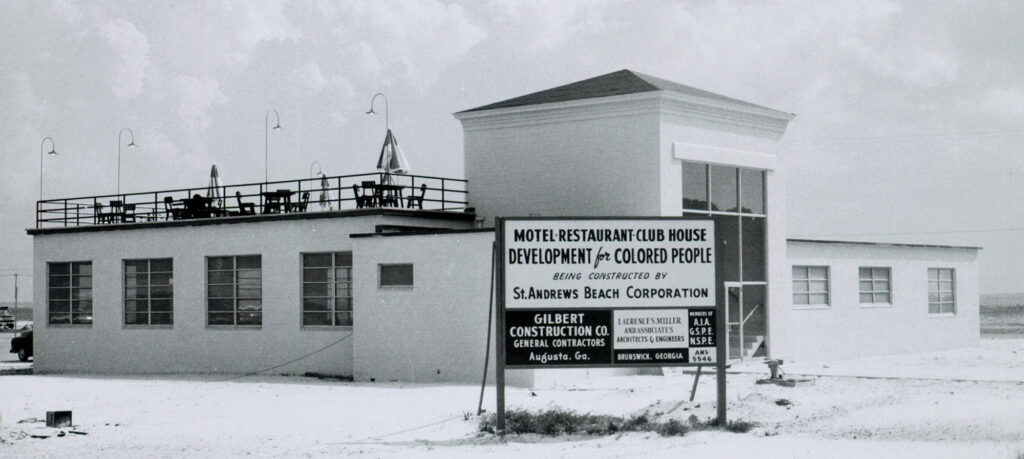

From her home in College Park, Georgia, south of Atlanta, LaVances Givens rattles off fond memories of Jekyll Island during the summer of 1959. Fresh out of her first year at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University, following its 1988 merger with Atlanta University), the Savannah native spent the summer as a cashier in the dining room of the new Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel. She stayed there with several other student workers, most of whom were from Macon. Among the crowd, she met a head waiter who would become her husband.

The Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel was situated on St. Andrews beach, the only spot in segregated Georgia where Black people were allowed to come in contact with the ocean. It was a vacation hub for Black families and a hangout for locals, who often held picnics and reunions there. “People just came by the droves,” Givens recalls. “You couldn’t even see the sand.”

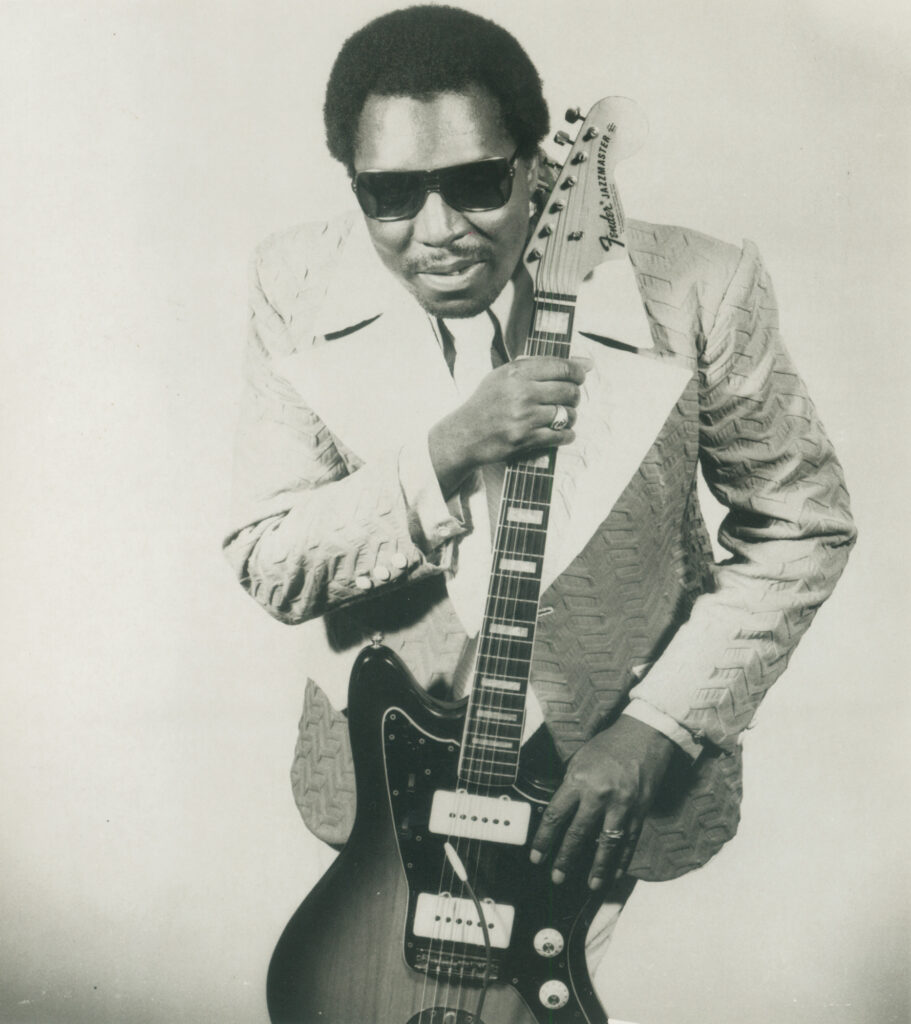

St. Andrews became more than a simple summer hangout, though. It also served as a regular stopover on the Chitlin’ Circuit, the informal name given to a series of venues, many in the South, where African-American musicians and entertainers performed to black crowds during the Jim Crow era. Local historians say blues great B.B. King and Georgia-born Otis Redding were among the national acts to perform at St. Andrews beach on the circuit.

Few outside of the area know the history of the historic beach and facilities that dotted the section of the coastline on the southern side of Jekyll Island. That’s due, in part, to the relatively short-lived heyday that the place enjoyed. It might also be attributed to the fact that many of the more traditional news outlets of the time—the white-owned and white-run press—didn’t take an interest in what happened there.

When it opened to the public in August 1959, the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel became the only hotel where Black visitors could stay, sitting steps away from the only beach on Jekyll Island where Black patrons were allowed. A couple months before its unveiling, on June 28, 1959 the Atlanta Daily World—the first successful African-American newspaper in the United States—ran an advertisement for the new inn. The ad boasted a hotel of “50 luxurious rooms and suites” with wall-to-wall carpeting, air conditioning, televisions, and telephones in the rooms. A month later, the World noted the significance of the establishment’s location: It sat near the spot where the slave ship Wanderer, in 1858, became the last vessel to bring enslaved Africans to Georgia.

The dining room at the hotel, Givens recalls, could hold about 50 patrons. It featured a slot machine that took dimes. “It might have been illegal,” she says now, laughing.

But the biggest draw of the complex may have been the Dolphin Club Lounge. Tyler Bagwell, a speech communications professor at the College of Coastal Georgia in Brunswick, has written two books and released two documentaries on the history of Jekyll Island. In an article on segregation on the island, Bagwell described the lounge as a “dance floor with a horseshoe-shaped bar and a small stage in one corner of the room.”

In the early days of the Dolphin Club, Givens remembers Atlanta jazz organist Cleveland Lyons regularly playing at the lounge on weekends. Before long, national artists stopped by, too.

White performers who came to Jekyll Island often played at whites-only places, including an auditorium in the Historic District and the grand Aquarama, a combination convention center/entertainment complex with meeting rooms and an Olympic-sized heated swimming pool. After the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel opened, Black performers and the patrons looking to see them had the Dolphin Club Lounge. But that soon changed.

A step toward equality

Dr. J. Clinton Wilkes’s request to host a large gathering of Black dental professionals in 1960 resulted in the construction of an auditorium to be built near the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel, to satisfy the legally dubious “separate but equal” doctrine that grew out of the adoption of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution almost a century earlier.

The Jekyll Island Authority quickly constructed a simple building, christened the St. Andrews Auditorium. Through the early ’60s, the auditorium was used for family reunions, dances, and the occasional concert.

With the beach pavilion that had opened there in 1955 — complete with dressing rooms, a concession stand, and a covered picnic area — the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel, the Dolphin Club Lounge, and the new auditorium at St. Andrews beach, the area quickly became a resort area for Black families throughout the state and beyond.

Jekyll Island—mainly the Dolphin Club Lounge and the St. Andrews Auditorium (as bareboned as it was)—also grew into a stopover on the Chitlin’ Circuit. In an interview conducted by the Jekyll Island Authority in 2013, the late historian Jim Bacote remembers “top entertainment of the era” playing the auditorium, which he described as “basically a tin building, and with no air conditioning.” Andrea Marroquin, Curator for the Jekyll Island Authority, said the museum has been able to confirm that, along with Redding and King, Millie Jackson, Percy Sledge, and Irma Thomas performed at St. Andrews beach.

According to Bagwell, concert promoter Charlie Cross brought Jackson, Sledge, Clarence Carter, Tyrone Davis, and Li’l Willie Johnson to the Dolphin Club Lounge. Both the Jekyll Island Authority and Bagwell said Redding was the last big act to perform in St. Andrews Auditorium, in 1964.

As it turned out, the Circuit didn’t last. Jim Crow laws were struck down by the mid ’60s, most notably through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the ensuing years, the island integrated and most of the venues closed.

Today, Givens has lost touch with many of the people she remembers from her time at the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel. Several have died. But she hopes those memories of St. Andrews beach are not lost to future generations.

“It’s a part of the history of the island,” she says.

St. Andrews Desegregates

From 1950 to 1964, St. Andrews beach served as the only section of Jekyll Island that allowed Black visitors. In an interview with the Jekyll Island Authority in 2013, historian Jim Bacote recalls a demonstration in 1963 in which he and several others attempted to enter a bath house in an attempt to desegregate the island.

Following Bacote’s death in 2018, the College of Coastal Georgia’s Tyler Bagwell told the Coastal Courier that others were denied access to a nearby golf course, the Aquarama’s indoor swimming pool, Peppermint Land

Amusement Park, and some motels. “A lawsuit was filed,” he said. “In June 1964 it was ruled that the state-operated facilities at Jekyll Island would be integrated.”

Bacote said the integration led to many of the Black-only establishments closing. “[W]ith us being able to go to the Aquarama,” he said, “we didn’t want to go down [to St. Andrews] anymore.”