By Josh Green / Photography by Brian Austin Lee

The reimagined Museum of Jekyll Island offers a mosaic of artifacts across human and natural history

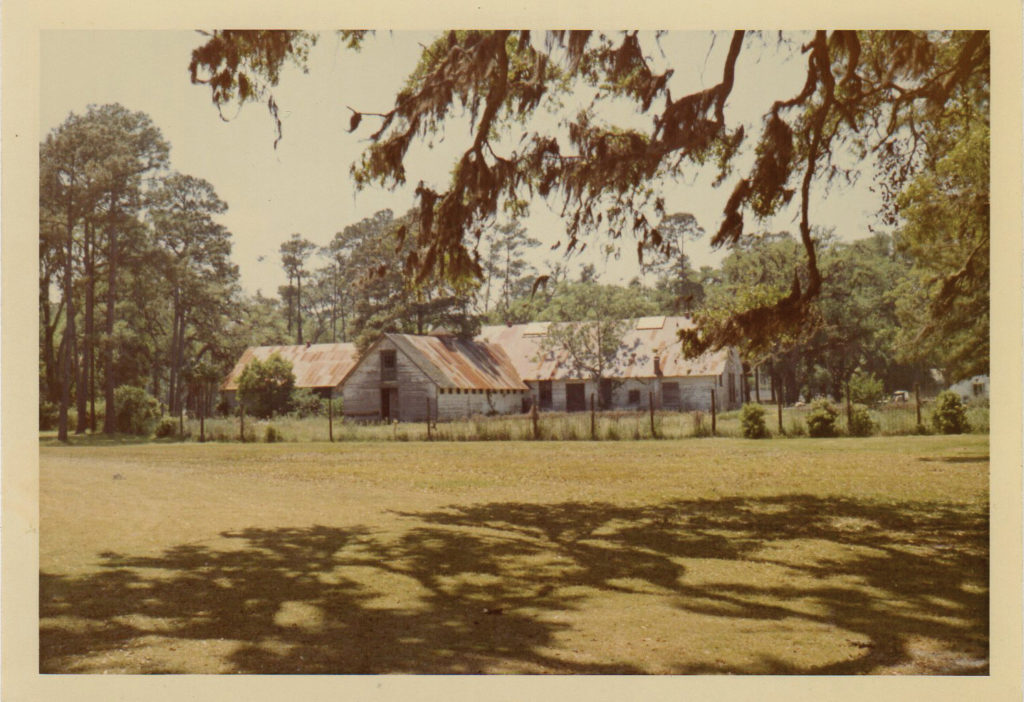

One breezy December afternoon at the eastern edge of Jekyll Island’s historic district, an unassuming white building that could pass for a country barn was abuzz with hammer pings and the shouts of construction crews. The workers had gutted the surprisingly airy, 9,000-square-foot interior to its inimitable bones. And if the wooden walls, towering fireplaces, and original double-hung windows could talk, they might recall: being built as the Jekyll Island Club Stables in 1897 for workhorses (and later automobiles) belonging to the likes of Joseph Pulitzer and the Rockefellers; serving as an inglorious storage facility for maintenance equipment and then a hardware store; and finally becoming a museum without air-conditioning or heat in the 1980s. That last incarnation had a paddock (with pervasive equine odors) and a boxy theater in the middle that obliterated the space’s charms.

Thanks to a $3.1 million renovation, the future of Mosaic, the Jekyll Island Museum, looks decidedly brighter. The goal of the project was to modernize the museum in function and flow while highlighting its architectural character, luring everyone from tykes to older history buffs and providing interactive, educational experiences that cover Jekyll’s history.

Up to 50,000 annual visitors are expected to use the museum as a gateway to the historic district—and to a greater understanding of Jekyll’s distinctiveness. “It really is an excellent example of the kind of revitalization that’s been taking place on Jekyll for about ten years,” said Bruce Piatek, the Jekyll Island Authority’s director of historical resources. “It’s the last piece, the last major redo in the historic district.”

Fundraising efforts for the public-private partnership, driven by the Jekyll Island Foundation, began in 2014. Joining more than 260 corporate, foundation, and individual donors, the Jekyll Island Authority contributed 1.1 million, while the Atlanta-based Robert W. Woodruff Foundation donated another $750,000. The design will reflect what the name Mosaic signifies: various facets of Jekyll’s story—nature, history, ecology—compiled as a single narrative under one roof. Climate control means hundreds of artifacts can now be displayed at once.

Inside, an array of sculpted migratory birds will dangle overhead as visitors work back through Jekyll history, beginning with Native American habitation. A circular playscape for kids will expand into the lobby and offer an oversized eagle’s nest and crawl-through marsh exhibit. Other pieces will include a Red Bug beach cruiser, a 1740s reproduction sailboat, a dugout Native American canoe made of Jekyll pine, and a replica hull of the Wanderer—one of America’s last documented slave ships, which landed on the island—that allows visitors to crawl inside and experience the inhumane conditions.

The museum isn’t meant to stand in for real experiences—such as spotting actual bald eagles—but rather serve as a starter kit for exploring the island’s rich history and natural beauty.

State era Refurbished Studebaker

Among the first treasures to greet Mosaic guests will be a restored four-door 1947 Studebaker—the type of car a family might have used to cruise the new causeway into Jekyll in the 1950s. Accompanied by a vintage Jekyll postcard expanded into a mural, the vehicle will serve as an interactive photo op; guests can sit inside and enjoy period music and a couple of old radio ads, including one celebrating the causeway’s grand opening. “We’re trying to put you in that setting,” said Piatek. “Initially, we were going to cut the poor [car] in half, but it was so pretty, we couldn’t.”

Club era Louis Vuitton luggage

Harking back to a time when one-sixth of the world’s wealth was represented on Jekyll each winter, this collection of leather-wrapped Louis Vuitton luggage (two trunks and a smaller valise) was as fashionable in name in the early 1900s as today. The pieces belonged to a Club family, the Jenningses of Standard Oil prosperity. Keep an eye peeled for old shipping labels still stuck to the sides.

Plantation era DuBignon signet ring

This heirloom signet ring from the DuBignon family—French émigrés who owned Jekyll Island for about a century until the 1890s—was handed down through generations and donated to the museum. Made of flecked stone and gold, the ring depicts the couronnes des comtes crown, wheat, and laurel leaves representing victory, triumph, success, fame, prosperity, and peace. “We have very few artifacts from that time period, and it’s directly connected to the family,” said museum curator Andrea Marroquin. “It’s a neat piece.”

Colonial/European era Major Horton’s uniform

Authentic in colors and wool material, which was believed to whisk away sweat in sultry climates, this replica uniform mirrors what would have been worn by Major William Horton, Jekyll’s first English resident, at the oldest Colonial-era structure on the island, the 1743 Horton House. Horton rose from civilian ranks to second-in-command behind General James Oglethorpe, founder of the Georgia colony, and the mock regalia reflects

that status.

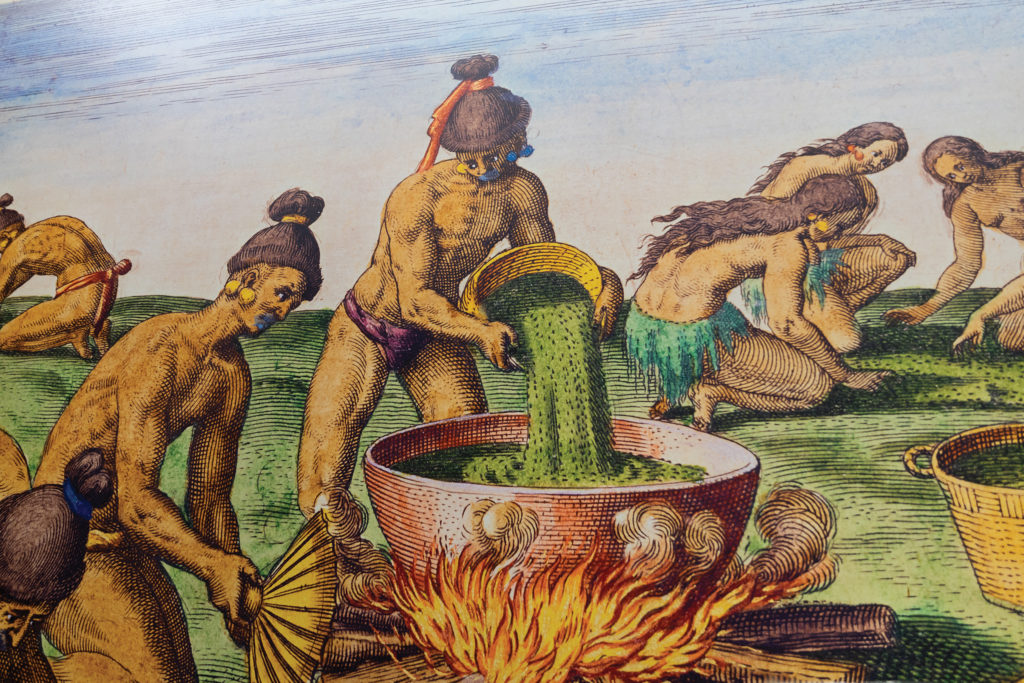

Native American era “Hidden in the Midden”

Anchoring the exhibit farthest from the entrance are re-creations of a Native American midden (refuse pile composed largely of oyster shells) and a thatched-roof cottage with mud and clay walls. Showing deposits by Archaic people from 4,500 years ago as well as ancestors of modern-day Creek tribes and other Native Americans, the three-dimensional midden provides an archaeologist’s perspective of deep sand, armadillo tunnels, even litter. A key message will be sustainability and stewardship, which the Rockefellers didn’t know to practice when they removed part of a shell midden in the 1910s to improve the marsh views at Indian Mound Cottage. Combined with a variety of artifacts, the installations will relay the story of bygone Jekyll residents who left no written record.