For Jekyll’s former live-in lifeguards, the season was filled with the magic of young people set loose in paradise.

By Tony Rehagen

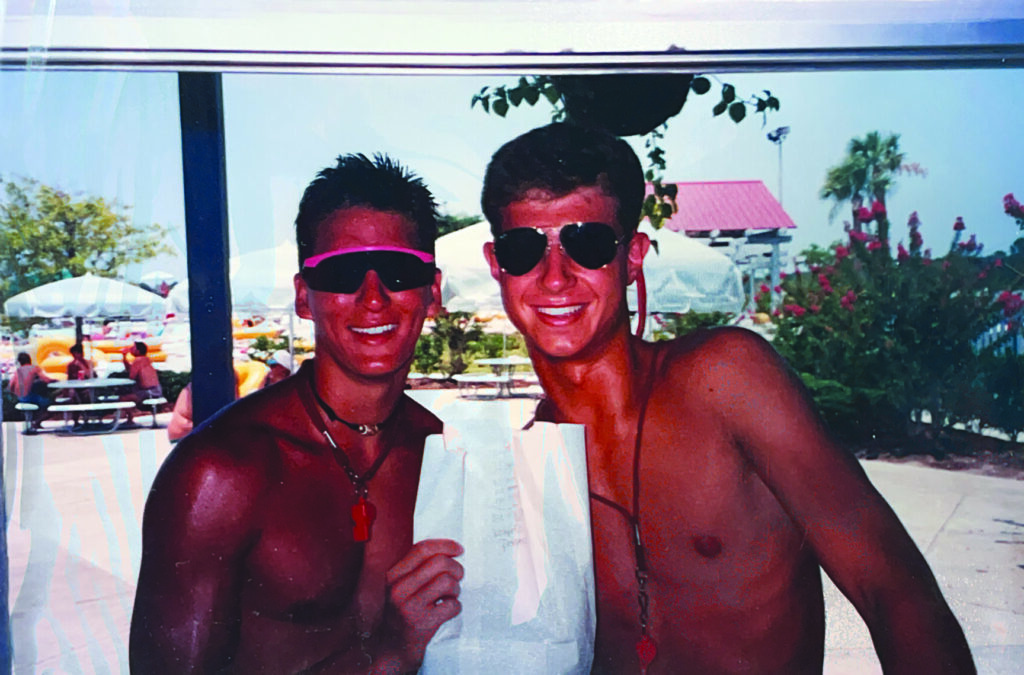

Photography by Buffy Jobe

At the start of the summer of 1997, in what was to be Erin Young’s second straight summer working as a lifeguard at Jekyll Island’s Summer Waves Water Park, she made a decision. The previous year, fresh out of Wayne County High School, Young had commuted to Jekyll, back and forth every day, from her parents’ house in Jesup, Georgia. A year later, with two semesters of college wisdom already tucked away, Young resolved to skip the commute and live with the rest of the lifeguards on the island. She was not going to make the same mistake twice.

Part of Young’s reasoning was avoiding the hour-long drive between Jesup and Jekyll. Living on the island figured to save time, gas, wear and tear on the car, and it would practically guarantee that she was never late for pool duty. At least, that was the argument to her parents.

The other reason—maybe the real reason—that Young and dozens of other 18- to 24-year-olds decided to take up summer-long residence in dorms on Jekyll? Well … dozens of other 18- to 24-year-olds were staying in dorms on Jekyll for the summer. The lifeguards worked together in the sun and surf by day and, as young men and women will do, played together late into the night in a seaside paradise that they had largely to themselves. “You were on your own, without regulation, completely unsupervised,” says Young. “It was mayhem. I mean, mayhem on occasion.”

During summers in the last three decades of the 20th century, after most tourists had packed up their chairs and beach towels and headed home for the day, the young lifeguards of Jekyll Island chucked off their daytime responsibilities and reveled in their full-blown youthfulness. Parties were thrown. Beverages were consumed. Cigarettes were smoked. All-night ghost hunts, moonlight beach walks, and a grab-bag of pranks were staged. And, of course, many other activities that are unsuitable to recount in a family publication were committed. “Let’s just say a lot of us are quite thankful that was a time before social media and camera phones,” says Young. All the while, friendships were forged that endure to this day.

“It was wild, like Lord of the Flies with no supervision,” says Tina Rosario, who lived on island from 1996 to 1998. “We were all the same age, in the same situation. Everyone got along. We lived together, ate together, worked together. It was as much fun as I thought it would be and more. Those were three of the best summers of my life.”

LIVING THEIR BEST LIVES

Sammy Tostensen was an incoming high school senior when he first came to Jekyll as a lifeguard in the summer of 1971. Growing up in the Fancy Bluff neighborhood of nearby Brunswick, Tostensen’s family frequented the island on vacations and day-trip getaways, and he had come to know and admire the young men and women who worked the beach, the Jekyll Island Club pool, and the Aquarama, a now-defunct Jekyll Island landmark that housed the region’s first indoor pool.

At the time, the dozen or so lifeguards, both male and female, lived in a long-abandoned wing of the Jekyll Island Club hotel that, despite having fallen into disrepair, had individual bathrooms and window-unit air-conditioning in each room. In addition to sitting in the lifeguard chair, the on-island lifeguards, among other tasks, were charged with draining the naturally fed Club pool (scrubbing it clean of algae) and manually watering the fairways at the golf course. “I wouldn’t call it hard work, especially at that age,” says Tostensen. “It was more fun than anything.”

In their off-duty hours, Tostensen and his fellow lifeguards partied on the beach, played loads of free putt-putt on the miniature golf course, and hung out with other workers on the island, including the Georgia State Patrol troopers who policed Jekyll. “We were very friendly with everyone on the island,” says Tostensen, who would spend two more summers on Jekyll. The bonds between the lifeguards, many of whom came from different areas of the U.S. and would go on to various careers from lawyers to millworkers, were particularly strong. “We were like a family,” he says. “And yes, there were always summer romances on the island. Some of them lasted, and some of them didn’t.”

Of course, unchecked youth has its way of getting into mischief, too. Glynn Bennett, who lifeguarded with his childhood pal Benjy Hodges (a future state trooper) in the summers of 1978 and 1979, remembers skinny dipping in a hotel pool after hours. On another night, he hopped the fence at the Aquarama and climbed to the top of its pointed roof. He was in on kidnapping the big dinosaur from the putt-putt course, too, and dragging it across the street, where it welcomed his bleary-eyed colleagues the next morning from a perch atop the lifeguard hut. “I’ve noticed they’ve bolted the dinosaur down these days,” says Bennett.

The Jekyll Island Club reopened as a luxury hotel in 1985, so lodging for the lifeguards was moved. Two years after that, Summer Waves opened, increasing the demand for waterside staff. By that time, the sleeping arrangements for the men and women lifeguards, all Jekyll Island Authority employees, had changed. Male lifeguards occupied the two-story building behind the Club that now houses offices for the JIA, the state entity that oversees the management of the island. Each large room was furnished with a couple of bunk beds. “It was a special place,” says David Berryhill, a lifeguard on Jekyll from 1989 to 1992, “once you got past the roaches and the communal showers.”

The women stayed on the top floor of a three-story building next door, which is today a JIA annex. The first two floors of that building then were filled with theater students who put on shows at the old outdoor amphitheater. “They’d let us come to their shows for free, and we’d let them come into Summer Waves with our passes,” says Rosario. “We watched all kinds of musicals.”

There were no TVs in the dorm rooms, but radios blasted music late into the night. The only other luxuries were the window-unit air conditioners, mini-refrigerators, and microwaves to cook frozen dinners, burritos, and the age-old young-person food staple, ramen noodles. Those cheaper nighttime snacks complemented the burgers, hot dogs, fries, pizza, Cokes, and ice cream that the employees had easy access to at the water park.

Without cellphones in those days, calls had to be made from a pay phone on the third floor of the women’s dorm. A wall behind the phone became a collage of scratched and inked names and messages between lifeguards throughout the years: Remember 4th of July ‘95.

The lifeguards put in long hours during the day, but at night, the island became their playground. They walked the beaches, staged epic island-wide games of hide-and-seek, pulled some stunts, and even hunted for ghosts around the moss-draped trees in the Historic District. They’d encounter all sorts of animals; alligators, deer, armadillos, possums, and squirrels. “Raccoons would eat dried ramen right out of our hands,” says Rosario. And, being kids, they’d often stay up smoking cigarettes on the dormitory porches until sunrise.

“Now just the idea of doing that exhausts me,” says Young. “But I do remember the feeling that we were all there living our best lives. And at the water park, the EMTs weren’t dumb. When we came to work [the next day] looking a little hazy, they made sure we got hydrated and ready to work.”

FOREVER FRIENDSHIPS

In the early 2000s, demand for lifeguard housing on the island dwindled. A new bridge on the Jekyll Island Causeway replaced an old drawbridge, making commutes to and from the island much easier. Meanwhile, as the JIA’s need for administrative office space grew, the former dormitory buildings were commandeered and made into JIA offices. Today, no dorms remain, and the only lifeguards that work on the island are at Summer Waves.

For many of the lifeguards who roamed the island back then, though, those summers—magical seasons of camaraderie, adventure, and newfound freedom—have helped shape them as adults. “It was a formative experience: You had independence, but you were not yet unleashed on the world,” says Young. “You learned that you could do what you want, but you still needed to show up to work.”

The bonds that were formed in those dorms remain, keeping former lifeguards connected (often during social media these days) to precious memories and to the island itself. “A year ago, I had surgery, and four of the people who came to visit were people I met at Summer Waves almost 30 years ago now,” says Rosario. “I appreciate the friendships I made there. It was a last breath of freedom before real life and marriage and kids. I don’t think it could ever be recreated.”

Jekyll is Still Wet and Wild

Here are three places to beat the heat.

SUMMER WAVES

Summer Waves Water Park has been keeping locals and tourists cool since 1987. Guests can brave the high-speed thrills of Man o’ War or grab a tube and enjoy a relaxing float around Turtle Creek. With more than a dozen water slides and a 450,000 gallon wave pool, there’s a full day of fun for everyone. The park is open seasonally from May-September.

OCEANVIEW BEACH PARK

Situated mid-island, Oceanview Beach Park offers stunning views and easy ocean access. Recently renovated to include an ADA-accessible beach entrance, shower facilities, and group pavilions, beachgoers can make a day of it by firing up the grill for a post-swim picnic.

BEACH VILLAGE SPLASH PAD

Newly opened in 2025, the splash pad offers an easy water activity for families with small children. This conveniently located attraction offers a quick cool-off option while shopping and dining. No lifeguard needed!