John Newkirt’s recollections paint a picture of a bygone era on Jekyll Island

By MARY LOGAN BIKOFF

Illustrations By MICHAEL FRITH

In the late 1940s, after Jekyll Island was acquired by the state of Georgia, as the opulent Gilded Age clubhouse first was converted into the 350-room Jekyll Island Hotel, guests arrived to the island via a 40-minute paddleboat trip from nearby Brunswick, Georgia. There to greet them—sometimes the first to do so—might well have been John C. Newkirt, one of the hotel’s bellmen.

Newkirt left his home in rural south Georgia in January of 1947—he was 17 years old—without a nickel in his pocket or a clear plan in mind. He landed on the island at a time when Black people couldn’t use the front entrance or stay at the hotel. There, for more than a year, he hustled from room to room, pouring Cokes and polishing wingtips for the ritzy clientele.

After his stay on Jekyll Island, Newkirt moved into the ministry, eventually traveling the world. In 1987, he became pastor of Johnson Grove Missionary Baptist Church in his hometown of Garfield, Georgia, where he served for more than 20 years. Now 92 and retired, he lives with his wife Ida in Garfield.

Newkirt’s memories of his time on Jekyll, excerpted here from a 2014 interview conducted for the island’s museum, offer a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the island in its early days as a state park.

Starting a New Life

In the early part of his life, Newkirt toiled long hours on his family’s farm for 50 cents a day. He grew frustrated with the pay and the hard work, so he hitchhiked the six miles or so from Garfield to Twin City, borrowed money to take a bus to Savannah where he learned of the job on Jekyll Island, then took another bus to Brunswick. He talks about his first night on island:

When I got off the boat … we couldn’t go in the front door. I went to the front desk to see Mr. Smith, who was the supervisor of the day shift, and I told him I was sent here from the department of labor for a job. He called, “Come here, Earl Hill”—that was the captain of the bell house [and the caddie for William and John D. Rockefeller]—”We got a man for you tonight.” Earl said, “Well, we have a job, when can you start?” I said “Now.” He said, “No, you got to get dressed first.”

The help lived over the stables. Earl said, “I’ll be back for ya about 10 o’clock.” Nobody had lived in that room I guess for months or whatever, it was just dust. I put my sheet and pillowcase on the pillow, then I got my bed ready and had a shower. I had a wrinkled white T-shirt on. Earl came back and said, “Now you going to have to have a white coat, do you have a black necktie?” I said, “I don’t have no black necktie.” He said, “I got one for ya.” He gave me a leather black necktie, and that was really something. I never had a leather black necktie.

The First Night Shift

For most of his time on Jekyll, Newkirt worked the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift, a time marked by late-night requests from the high-rolling vacationers on the island.

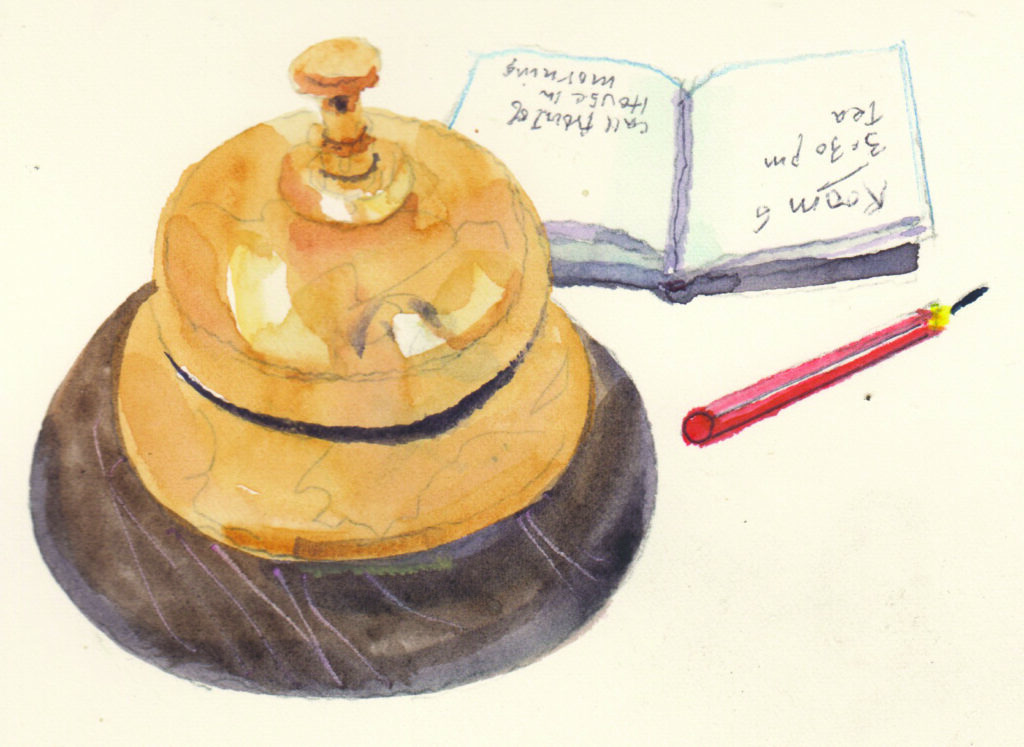

Eleven o’clock came and “Bing!” I didn’t know what the bell was for. “Front!” Mr. Smith now was ringing the bell for the bellhop to come to the front desk because he had to go to a room on the third floor to take some ice, ginger ale, and some Cokes. He wrote it on a little pad. But you had to make sure that you only picked up what he said because when anything was missing, I was responsible. And he said, “Always knock, identify yourself, do not open the door and go in.” I knocked on the door, “Who’s there?” I said, “Bellhop John. I come to bring you ice and drinks.” “Okay, come on in.” I went in, opened the drinks, opened two sodas, one ginger ale, and poured this pitcher full of ice. When I got finished, they handed me 50 cents. That was a day’s work right there [in his hometown of Garfield].

I kept getting “Bing! Front desk!” I know where now; up, down, north, south. And I did that until 7 a.m., because they were gambling all night.

My time was up [after his shift], and then you come down and eat breakfast before you go. Oh, I was so hungry. Hadn’t had nothing in two days. I ate grits, sausage, eggs. I mean, when I say eggs, I mean four or five eggs [laughs], four slices of toast. I didn’t drink coffee, I had two glasses of milk. And now, I’m full, I’m going to bed.

A Handsome Salary

On his first night on Jekyll Island, according to another interview Newkirt gave, he made $7.30, almost three weeks of pay on his father’s farm. And that was just in tips.

We got paid twice a month, the 1st and 15th. Fifteen dollars on the first two weeks, and 15 dollars on the second two weeks. I only took mine one time and I told Ms. Culpepper—she was personnel, the banker, the post—I would not sign up any more because I was getting too much money. I didn’t know what to do with this money. I couldn’t put it in the bank because Black people didn’t bank here. So she saved it for me in a big brown envelope. Oh, I had so much money. Each night I was making more and more, ’cause I was doing it faster and faster.

On the Town

In another interview, Newkirt describes his work uniform; white shirt with a black leather necktie, dark trousers, black shoes, and a white coat with blue cuffs and a blue collar. After he earned some money, he went shopping.

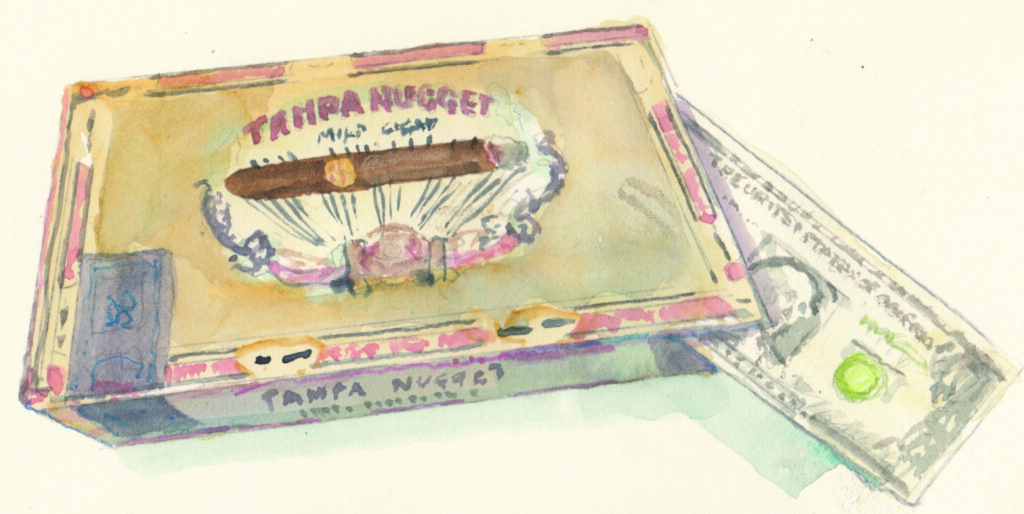

Now I didn’t have no clothes except what I had on my back when I came here. So, one Friday, I went to Brunswick. I took my Tampa Nugget cigar box, what I had my money in, and I went to an exclusive men’s shop. Oh, this was a men’s shop that was out of this world. Nice neckties, shirts, you name it. I bought me five short sleeve shirts, four pair of pants, I guess 10 or 15 pair of underwear, top and bottom, socks. And then, I had to go to a shoe store where they sold shoes for big feet [laughs]. When I got there, he went and got me a 13 triple E, a black one, and I slid my feet in there. He said, “This here shoe is $2.50, but since you have 13 size shoe, you have to pay a dollar extra.” I bought me a brand-new black leather tie, for 50 cents, bought me a brand-new bow tie for 25 cents, leather. So now I got a brand-new shirt, brand-new black tie, brand-new pants, and brand-new shoes. I am dressed to kill.

Race and the Island

Coming to Jekyll, Newkirt traveled in the Black-only area of the boat. While on the island, he lived upstairs in a former horse stable that had been converted for use by the Black workforce. He worked with many older men and women, some of them the sons and daughters of former slaves, and many of whom had no education. Newkirt had a 10th grade education and helped many of them out with their paychecks and purchases.

I didn’t know anything about racism. I never heard that word until the ’60s. I thought that’s just the way it was. I didn’t know. I felt I had everything I needed, everything I wanted. I’m well employed. But when I left here, this hotel was now going into change, from Jekyll Island Hotel to Jekyll Island State Park. Mr. [Herman] Talmadge was the governor, and what made me so angry leaving here, Mr. Talmadge made a remark that the Negroes ain’t worth but 50 cents a day. And anyone wears overalls, that’s all they will get as long as I am governor. [Deep breath] But I thought about Mr. [Thomas H.] Briggs [Jr., the manager of the Jekyll Island Hotel], Mr. [W. Red] Weatherford [the hotel’s assistant manager], who were the two top men I was under and answered to. They treated me, I would say, as they would any other person, white or Black.

Letters From Home

With the exception of a brief foray into Brunswick, Newkirt spent most of his time on the island, working. Occasionally, he did hear from home.

Ida Belle wrote me a letter. She said, “Dear John, I have moved, and I do not live where I had lived before.” I misread the letter. I thought she was saying, “Dear John, I have married, and I do not love you anymore.” I balled it up and I started to tear it up, but something said don’t tear it up, and I put it in my pocket. So, me and Fuller, a friend of mine, a bellhop on the day shift, went down to play horseshoes, that was our game. So I took it out and read it, and something said read it slow. And it said, “Dear John, I have moved from where we used to live and I don’t live there anymore. This is my new address, if you want to write me, please write me the route through Millen, Georgia [a small town in Jenkins County, south of Augusta]. I love you honey, bye bye.” Oh boy [laughs]! I sat right down then. I was a 10th-grade student, I had very good handwriting, and I wrote her a darling letter. “Dear Darling, I have received your letter today. I am so glad to hear from you and I love you. Thank you so much for writing me. I don’t have time to write you because I am on the job tonight, but I will write to you a little later when I have time.”

More than 60 years after leaving Jekyll, Newkirt and Ida returned to the island, where he was feted by several people at the hotel. “This is not a book of fiction, it’s a book of facts,” he told an interviewer at the time. “I learned on Jekyll Island what you can be if honesty is on the top of your list … to all the staff who treated us so kind, thank you Jekyll. You have made my life; not just my day, you have made my life.”