Nature continually shapes the island. That’s healthy, and a little scary, too.

By JOSH GREEN

Illustrations by ANDY LOVELL

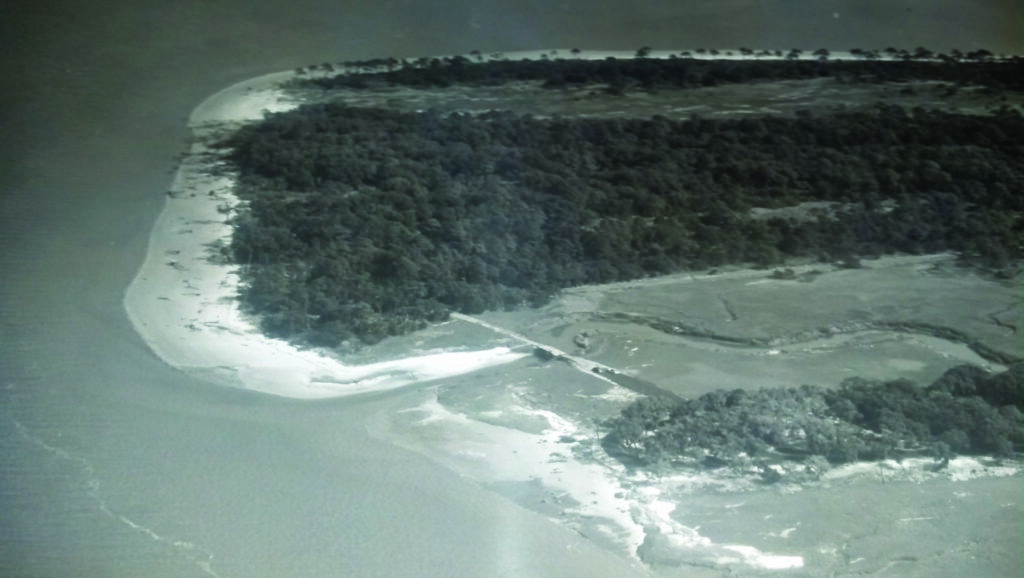

Like all of Georgia’s 14 barrier islands, Jekyll Island is dynamic. It’s a 5,700-acre composition of sand, soil, and flora upon which wind and tidal forces constantly act, causing the island to both grow and shrink. The changes come in two primary ways: Either through erosion (Driftwood Beach, that picturesque boneyard of ocean-toppled, petrified trees didn’t technically used to be where it is today, but closer to Jekyll’s pier and the island’s extreme northern tip, roughly a mile away), or through accretion, the gradual addition of new land packed on at the beach and salt marshes.

The best example of accretion today is on the island’s south end, which historical records show has extended half a mile southward since 1867. (It’s grown by 500 feet just since 2002.) Beachside homes on that part of Jekyll built decades ago now require a long walk or drive to the sand. Elsewhere, the undulating topography around Camp Jekyll, as one example, consists of old beachfront sand dunes that have stabilized and grown vegetation. At nearby St. Andrews Beach, erosion is starting to claim upland ground and oak trees and create a miniature version of Driftwood Beach.

Two habitats are competing and, as always, the ocean is winning.

Another stark example: A couple of generations ago, the North Picnic Area, as 1960s postcards depict, was a hotspot for vacationing families. With views to St. Simons Island across the sound, the recreation area included spots for shaded lounging, benches, and large concrete picnic tables set back from the waves. According to board minutes from August 1964, the Jekyll Island State Park Authority unanimously voted to install 1,200 feet of rock near the picnic area to protect against the sea. But the vote came too late. The following month, Hurricane Dora swept up from Jacksonville and caused heavy damage to the North Picnic Area—if, in fact, Dora didn’t wipe it away entirely. (Board minutes never mention the picnic area again, and other records are scant.)

These days, when tide conditions are right—or if another storm lifts away sand on Driftwood Beach, as Hurricane Nicole did in November—the picnic tables emerge from the sea, peeking up like oversized tombstones from an old shoreline.

Visible topographical changes to Jekyll are not just natural but expected, and in many cases totally healthy. The forces that cause them, though, are becoming more frequent and stronger, requiring manmade action and preventative measures, both obvious and not.

“You’ll see that changes flip flop sometimes on different parts of the island, erosion and accretion, showing that the growth isn’t constant, it’s always changing,” says Yank Moore, the Director of Conservation for the Jekyll Island Authority. “It all illustrates what the forces of change, the natural forces, can do.”

While some continue to discount the causes, severity, and even the existence of climate change, it’s clear that punishing natural forces are increasingly top-of-mind for Georgia’s coast. Jekyll Island, like many of its coastal neighbors, is being forced to come up with innovative solutions to adapt and prepare.

Moore says changes to Jekyll’s mature, protected maritime forest and marshes are detectable—mostly by noting basic plant succession and the transition of certain habitats—but are slow enough to be of relatively little concern. Sea levels throughout coastal Georgia are a different story. Historical data show that high-tide flooding events were rare until about 1990 (less than one per year). Between 2010 and 2019, that jumped to 6.5 events per year. The first two years of this decade have seen 11 tide-related floods a year.

By 2050, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts the number of events could swell to 70 per year, or roughly one every fifth day, according to Kelly Hill, Georgia Department of Natural Resource’s green growth specialist.

High-tide floods exacerbate the erosion and wreak havoc on infrastructure up and down the coast, says Hill. That isn’t limited just to beach erosion or damage to docks and other structures on the wetlands side of Jekyll, especially when big tides combine with storm events. “We have a lot of people,” Hill notes, “that drive through salt water pooled on roads, unaware it’s damaging the undercarriage of their car. Those are things that people are going to really have to start thinking about.” Moore says sea level rise hasn’t been as damaging on Jekyll as in other coastal areas, but “we are seeing more of those bigger tides, over that nine-foot level.”

On the major storm front, Georgia’s 100-mile coast has been impacted by 11 tropical storms and one hurricane across the first two decades of this century—more than the total between 1950 and 2000. “I think people who’ve been there the past decade have noticed impacts from more hurricanes—Matthew, Irma, Ian, and Nicole—with visual changes they’ve seen on the shoreline with sand dunes,” says Hill, who’s based in Brunswick. Still, hurricanes do provide some benefits, from a biological perspective, in that they can reset beach ecosystems and make it easier for species such as sea turtles and shorebirds to flourish. “A hurricane knocking back some vegetation, and throwing a bunch of new sand up there, is actually a good thing, even though they might look destructive, and they are, from a human standpoint,” says Moore. “We had one of our most productive shorebird years with our Wilson’s plovers—a species that nests [on Jekyll’s southern end]—following a hurricane, because it gave them a lot more room to spread out, and kept the predators away. Sea turtles nest on dunes and open sand, but with vegetation, roots and things can constrict the growth of their eggs. The reset that hurricanes provide is good for turtles’ success.”

Is there anything that Jekyll visitors and residents can do to help stem the tide of change? Hill recommends diligently obeying educational signage and warnings posted around sensitive areas. “People don’t understand how fragile the sand dune system is, and how important it is to protect our shorelines from erosion,” she says. “Don’t wander into the dunes and trample vegetation.”

Professional mitigation measures are nothing new on Jekyll, and they continue. (See the so-called Johnson rocks, an abetment of granite boulders stretching down the island’s east coast to slow erosion, originally installed in the 1960s after Dora and recently restored.) More recent flood-fighting upgrades have come ashore, from bioretention areas and functional landscaping that helps keep soil in place, to permeable concrete in several places around the island, gravel bike trails, and permeable pavers that help water infiltrate the ground and relieve the burden on stormwater infrastructure. Elsewhere, bioswales in hotel parking lots, Hill says, are mistaken by visitors as gardens. (Bioswales are designed to control stormwater runoff.) Another tactic by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is more experimental; it involves dredge material pulled from the bottom of Jekyll’s intercoastal channel that’s sprayed evenly over the marshland to raise its elevation, if only slightly, in the face of sea-level rise.

Yet another measure that could have a broad, positive impact is Jekyll’s adoption of a sea-level ordinance last summer mandating that future development be raised a specific height, per DNR recommendations, to accommodate for more frequent flooding events. Jennifer Kline, Georgia DNR’s coastal hazards specialist, says Jekyll’s government was the first in the 11-county coastal area to implement such an ordinance.

“Jekyll is not unique in its vulnerability on the coast,” says Kline. “But, where Jekyll is unique is that they are being extremely proactive and have really stepped out front recently to address some of those vulnerabilities. Continuing down that path is a positive step forward in being able to adapt.”

Stormy Jekyll

Are big storms becoming more and more frequent around Jekyll?

Impactful storms have come ashore throughout the island’s existence, but the terminology for them has changed over the years. These days, according to the National Hurricane Center, a tropical storm is defined as a tropical cyclone (a cyclone is a “rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation”) that has maximum sustained winds of 39 mph to 73 mph. A hurricane is a tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 74 mph or higher.

Here’s a summary of hurricanes and tropical storms in the area over the past 163 years.

- Historical records indicate nine hurricanes struck coastal Georgia from 1851 to 1900.

- Five hurricanes were logged from 1901 to 1950, when “tropical storm” designations began.

- Just one hurricane (Dora) landed from 1951 to 2000, but 10 others were classified as tropical storms.

- This century, two tropical storms were recorded from 2001 to 2012, but no hurricanes.

- Since 2012, the coast has seen just one hurricane make landfall, though at least four have had a significant impact on Jekyll. Nine tropical storms have struck in the last decade.