By Osayi Endolyn

How the disappearance of turtle soup, once an American culinary staple, reflects Jekyll Island’s modern evolution

Among recipes for calf’s head soup and oyster gumbo, Abby Fisher included instructions for green turtle soup in her notable 1881 collection What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking. A formerly enslaved woman from South Carolina who’d launched an award-winning preserving and pickling career in San Francisco, Fisher was unable to read or write, but she dictated her expertise with authority: “To two pounds of turtle add two quarts of water, put to boil on a slow fire and cook down to three pints.” The reader is instructed to place thinly sliced hard-boiled eggs at the base of a serving dish, add “a gill” or about half a cup of sherry wine, then pour the salt-and-pepper-seasoned soup tableside while piping hot.

In St. Louis, widowed housewife Irma Rombauer featured a recipe for green turtle soup in her best-selling tome, the Joy of Cooking, first published in 1931. The 1975 edition was updated by Rombauer’s daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker, and is considered the classic among eight iterations that refined the matriarch’s quirky voice and cooking process. In it, she encourages the home cook to consider canned or frozen turtle meat to save time. Of course, “if you can turn turtles, feel energetic and want to prepare your own,” the recipe headnote says, just follow along. The home chef is forewarned that handling “these monsters,” which can reach 300 pounds, is not the typical domain of the residential chef. But if you must, “put them in a deep open box, with well-secured screening on top; give them

a dish of water, and feed them for a week” to rid them of the waste of their natural habitats.

It can be difficult to reconcile the celebrated iconography of sea turtles throughout the Southeastern barrier islands with an American appetite that historically indulged in consuming the same species. Once considered a delicacy, turtle soup has become a rarity since Fisher and Rombauer documented popular recipes of their day (as has mock turtle soup, often an offal-based version). But for much of the twentieth century, the dish held an esteemed place in haute cuisine and home kitchens alike. The Golden Isles were no exception.

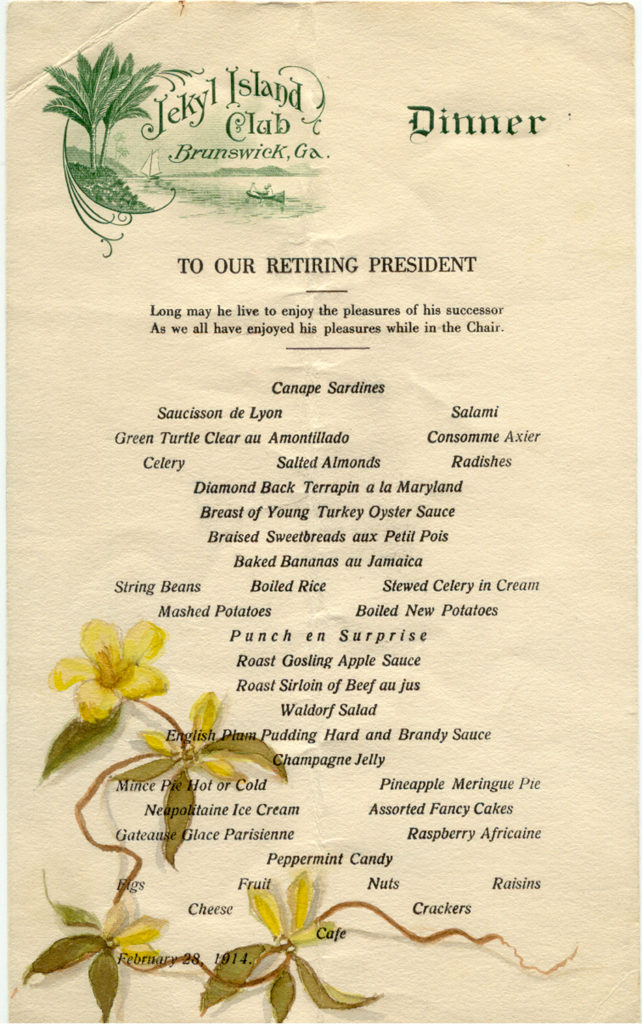

Archives from the Jekyll Island Club reveal that turtles were regularly featured on the menu from at least 1912—President Taft was in office then; he adored turtle soup—to 1941. At a dinner celebrating a retiring official in 1914, the club pulled out all the stops. Along with English plum pudding, turkey breast in oyster sauce, baked bananas au Jamaica, and pineapple meringue pie, the menu included both “Green Turtle Clear au Amontillado” and “Diamondback Terrapin a la Maryland,” a Baltimore dish served with Madeira and sweet cream.

In America, turtle soup’s rich taste—generally speaking, a combination of alligator meat’s texture with duck’s gamey flavor—had won over fans from the perch of the presidency (Washington, Adams, Lincoln, and Truman) to the traveling set on railway dining cars on down to the Campbell’s soup crowd in the 1920s. In its finest settings, the slow-stewed preparation was served with a side of sherry that helped cut the fat while imbuing the dish with a sense of decadence. But the soup began to disappear from American menus, prompting some historians and culinary scholars to ask why.

One observation was that Prohibition in 1919 took fortified wine off the table, rendering one of the most important ingredients unavailable and illegal. Historians have argued that the collective pause in (legal) alcohol consumption actually helped turtle populations rebound. As industrialization took hold following the Great Depression, Americans’ tastes were shaped by animal meat that was easy to farm, process, and cook: chicken, pork, and beef. Turtles sized appropriately for eating often yield just three to four pounds of meat, to say nothing of the intensive butchering process. Over time, turtles were considered too much work and in many areas retained the whiff of poorer, harder times.

One of the simplest explanations, however, came from Dr. David Steen, research ecologist at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center (GSTC) on Jekyll Island, who wrote definitively in Slate, “There aren’t enough turtles left to eat.” His 2016 opinion piece was a response to a Saveur essay by Jack Hitt from late 2015, in which Hitt accompanied a group of turtle hunters on their annual trek in southwestern Virginia. Hitt brought the reader along on a vivid “cooter hunt” replete with muskrat dens, muddy river water, and plenty of twang. “We were after big turtles with shells the size of dinner plates or steering wheels, heads the size of a man’s fist, and a mouth big enough . . . to guillotine a finger in one swift motion,” wrote Hitt. He linked Americans’ diminished taste for turtles with their tendency to anthropomorphize them into “a loveable cartoon character—see: Yertle, Franklin, Cecil, and Touché, not to mention Donatello and that whole gang.”

But Steen felt one key element of the conversation was missing. Sea turtles—such as the green ones that appear in myriad American cookbook recipes—are federally protected by the Endangered Species Act. About half of all turtle species, including freshwater turtles and tortoises, are threatened with extinction. According to Steen, we flat-out ate turtles into near nonexistence, an inevitable result of prizing egg-producing females for their tastier meat. “Turtle soup in the United States did not fade away simply because our palates changed,” he concluded. “Our taste for turtle soup exploded to unsustainable levels and caused the turtles to disappear first. They still haven’t come back.”

There were some who noticed the connection, however, almost twenty years before Steen’s article. When Scribner reissued Joy of Cooking in 1997 and included the historic turtle soup recipes, activists were in an uproar. “Gather round the cookbook-burning bonfire, folks,” Heather McPherson wrote in the Orlando Sentinel then. “A bunch of turtle huggers are upset over the Joy of Cooking.” Times had certainly changed.

Nowhere has the attitude toward turtles changed more than on Jekyll. In 1950, three years after the State of Georgia purchased the once-exclusive island, the Jekyll Island State Park Authority Act limited development on the island to one-third of the land. In ensuing years, Jekyll would become a sanctuary not just for all manner of wildlife but for marine biologists, University of Georgia ecologists, and environmentally minded AmeriCorps volunteers. In 2007, the GSTC opened in a retrofitted power plant in the island’s historic district. Under the gaze of tourists, researchers study and document the turtle species present on the island, working to develop ways to aid in their protection. Visitors can join scientists on nighttime ride-alongs to see nesting loggerheads mid-crawl, watch veterinary procedures in action in the center’s operating room, or visit sick and injured sea turtles in the rehabilitation pavilion.

The GSTC hopes that through research, education, and basic intervention, they can help limit the destructive impact of habitat loss and other human-driven threats to turtle populations. For example, the Jekyll Island Causeway sees up to 400 turtle deaths each summer as female diamondback terrapins cross high-traffic areas to lay eggs. At the start of every nesting season, the GSTC places flashing “Turtle Crossing” signs and installs predator-proof nesting boxes; their work has saved some 2,500 terrapins over the last decade.

A January report from the science journal PLOS ONE says environmental efforts supported by the Endangered Species Act are having a positive impact on turtle populations. Steen, for his part, says success is when “you don’t need to worry about the conservation of a species blanking out due to anthropogenic threats.” Turtles aren’t well enough to be left alone yet, even if they’re off the dinner table.

Well, mostly off the dinner table. Today, Pennsylvania allows limited hunting of its snapping turtle, but only after the females have laid their eggs each season. In New Orleans, where diamondback terrapins can be hunted under specific regulations, turtle soup still appears at classic French-Creole restaurants like Uptown’s Upperline and Galatoire’s in the Quarter. It’s a sharp contrast to the mindset on Jekyll, where injured terrapins bask in an outdoor sanctuary and sure-handed guardians relocate turtle nests at risk of predation or tides.

Who can say what renders a species inconsumable? Bluefin tuna and the Patagonian toothfish (also inaccurately known as Chilean sea bass) have been overfished for years, but that rarely stops seafood lovers from consuming them. If there’s one consistent trait of humankind throughout the centuries, it’s that we tend to put ourselves first. The proof is on our plates.

At the GSTC, Steen understands that most people define a species’ value in relation to what it does for us. An animal that spends much of its decades-long life submerged in water or hidden in swamps can be easily overlooked. But he wishes that wasn’t so. “We happen to be sharing this brief period of time with these fascinating creatures,” Steen said. “They’re the product of millions of years of evolution and we’re here at the same time.” That’s a marvel unto itself and good enough reason to lose your appetite.