You can’t visit them anymore, but these once-vibrant structures are worth remembering

By Wendell Brock

Archival images courtesy of the Jekyll Island Museum Archives

Jekyll Island has been shaped by time, nature, and human enterprise. It has survived fires, storms, and scandals—events hard to imagine when strolling through the National Historic Landmark District on a sunny day. Today, the manicured “millionaires’ village” is a major attraction and the focus of one of the largest ongoing preservation projects in the Southeast. Yet some pieces of the story have disappeared along the way. Here, we offer a look at three long-vanished structures from the island’s gilded glory days.

Solterra: A brief season in the sun

The owners were not there to receive their distinguished guests. but for a few days in the spring of 1899, the eyes of the world were fixed on Solterra, the gracious twelve-room cottage of New Yorkers Frederic and Frances Baker. While the couple traveled abroad, they offered their retreat to President William McKinley, who along with his first lady, his vice president, and the VP’s wife basked in the comforts of the Bakers’ sprawling winter idyll.

This was Solterra’s finest hour, but the gaiety was short-lived. In March 1914, the house went up in flames, never to be rebuilt. Baker, who owned an expansive portfolio of Manhattan warehouses, had died the year before, and his widow lost interest in the property, selling the creek-front estate to Richard Teller Crane Jr. In 1917, the Chicago plumbing magnate erected Crane Cottage, the opulent Italian Renaissance manse that’s now part of the Jekyll Island Club Resort, on the ashes of the Bakers’ lovely Queen Anne haunt.

Though Solterra is gone—only its dovecote and a planter remain—it maintains a hold on locals’ imaginations. The burning of Solterra inspired part of Almost to Eden, a novel by part-time Jekyll resident June Hall McCash. In the book, the young servant Maggie rushes into the smoldering cottage to rescue the only photograph of the owners’ late daughter. (In real life, the Bakers had a little girl who died as a child.)

There’s a good bit more to the Baker legacy. “It was [Frederic] who had the bright idea of building Faith Chapel,” says McCash, who is also a historian. Frances Baker was one of the few women who became a club member in her own right, and she was a generous benefactor of the island school.

But it was the McKinley visit that set the world on edge. “Jekyll Island has had the greatest crow in its history for the past few days,” the Brunswick Call reported of the presidential sleepover. According to Jekyll Island Museum curator Andrea Marroquin, the twenty-fifth president and his entourage enjoyed driving around the isle. “They got a chance to have some receptions with club members, who were obviously influential people, and that was probably a very sound political move,” she says.

As the new century dawned, McKinley was reelected to a second term. But by 1901, Jekyll was aflutter again; only this time, the news was horrific. The president had been shot. Eight days later, on September, 14, 1901, Solterra’s most famous houseguest was dead.

Red Row: Home of Jekyll’s unsung laborers

The African Americans who labored on Jekyll during the early twentieth century made the lives of the millionaires easy. They cooked and cleaned. They took care of the children, tended the gardens, drove the cars, milked the cows, and grew the food—often to the neglect of their own families back on the mainland.

By World War I, the Jekyll Island Club had trouble holding on to black employees, many of whom left for better-paying jobs. To address this concern and to provide lodging, the club built Red Row: ten simple wooden houses that employees could lease for a fifty-cent dock in pay ($1 instead of $1.50 a day). The name came from the red material, Barrett’s Roofing Felt, that covered the roof and exterior of the homes.

Over the next few decades, a community thrived on Red Row, segregated but peaceful. Citizens attended their own church, Union Chapel, which Faith Chapel had displaced in 1904. There was a school; a nearby commissary run by forestry foreman Sim Denegal, a revered community member; and a recreation hall boasting a piccolo (jukebox) brought to the island by Earl Hill, a caddy who later became a noted golfer.

Club members occupied Jekyll only a few months each year, so the inhabitants of Red Row led more leisurely lives when their employers were gone. They hunted wild hogs and turtle eggs, swam and played golf, held fish fries and dance contests. Sometimes a $50 prize was awarded to the best dancer, who might wow the group with the Charleston, the two-step, the Big Apple, or the Suzie Q. “Earl Hill traveled to Texas, and he came back with a dance he named the Heebie-Jeebies,” Marroquin says. Former Red Row resident Carrie Lee Robinson recalled neighbors coming to her house to listen to Joe Louis fights on the radio.

When the state took over the island in 1947, the inhabitants of Red Row had no reason to stay, and over time, their dwellings disappeared. (If they stood today, the homes would be adjacent to the old amphitheater on Stable Road.) By the late 1970s, the last remaining house served as a toolshed for the Jekyll Island Authority; now that is gone, too. “At this point, we don’t really know when or why the houses were lost,” says Marroquin, who hopes that an effort to compile oral histories of former employees will preserve the neighborhood’s legacy.

The water tower and windmill: A Magnet for storms

If you look at vintage photos of the Jekyll Island Club, you may notice a windmill and water tower looming over the compound—a singular sight, taller even than the main buildings. In 1891, the club opted to erect the tower and windmill (a low-tech water pump) to replace leaky water tanks in the club attic. The structures were ordered from A.J. Corcoran in New York, transported to Brunswick by rail, then ferried to the island.

The man charged with assembly was one Torkel “Chips” Torkelson, a Norway native who worked as a ship’s carpenter and was called on for many Jekyll building projects. The structures rose behind the clubhouse annex, to the east. By all accounts they did the job—until they got clobbered by weather. In 1896, club superintendent Ernest Grob wrote to Corcoran that his products performed beautifully, except during cyclones. Then came the 1898 Georgia Hurricane, the strongest storm in state history. After that debacle, which flooded the streets of Brunswick and wrecked newly built Chichota Cottage, Grob dashed off another letter to Corcoran: the windmill had been decimated, and he needed a new one.

As best as can be determined, the second tower and windmill lasted for the next three decades. Then came the tempest of 1928. “Apparently they lost a lot of the beach, and oak trees came down and the windmill was damaged,” Marroquin says. At that point, Torkelson’s handiwork was a wash. The structures were dismantled by the next year.

The Dairy

In its heyday, the club maintained a farm to supply dairy and eggs to the kitchens. All that remains of the farm is a grain silo, built of tabby in 1910. The silo sits in a wooded area just northeast of the airport off North Riverview Drive. It’s accessible by bike or foot only via an unpaved, unmarked trail just north of the multi-denominational church. (If you reach Jennings Avenue, you’ve gone too far north.) Look out for a squat fire hydrant at the path’s entrance.

Chichota Ruins

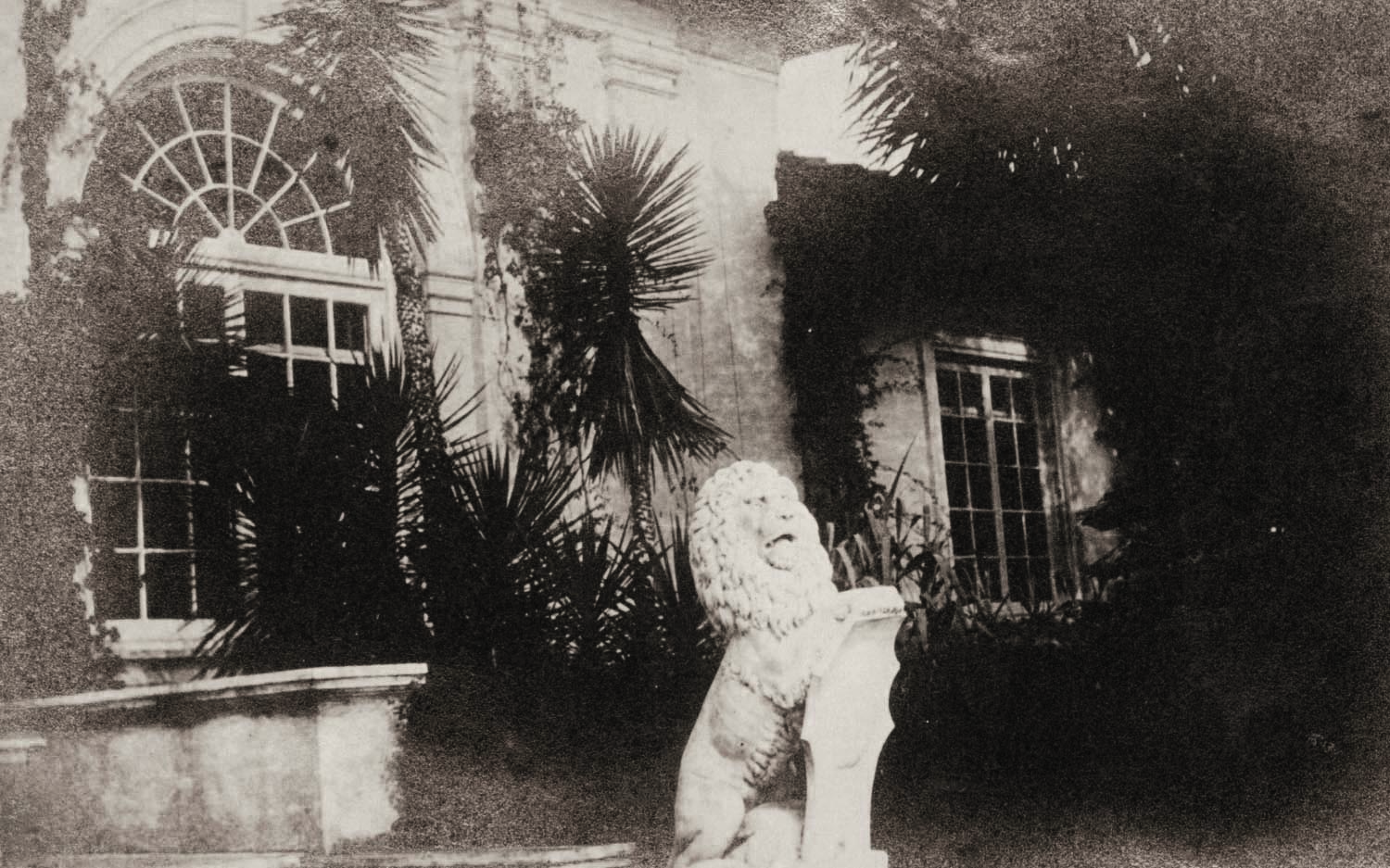

Built in 1897 for David H. King Jr., Chichota later became the home of Edwin Gould, son of railroad magnate Jay Gould. The house boasted a swimming pool and a playhouse known as the “Chichota

Casino” that held indoor tennis courts, a rifle range, and a bowling alley, among other recreational features. Today, little remains of Chichota except two large concrete lions, but the ruins are a lovely spot for taking photographs.

Find them just north of Crane Cottage, 375 Riverview Drive.