A remarkable volunteer restoration effort has breathed new life into a once-mighty mansion

By Scott Freeman

Eighteen years ago, Dick Tennyson made what he thought was a great deal. The snowbird from upstate New York agreed to volunteer for the Jekyll Island Authority in exchange for free golf. He even got to pick his task: the restoration of a long-abandoned cottage on the western side of the island.

“The house was beautiful to look at, but it was in bad need of attention,” says Tennyson, a retired electronics engineer who was sixty-two at the time. “I wanted to work on something significant, and that house was significant.”

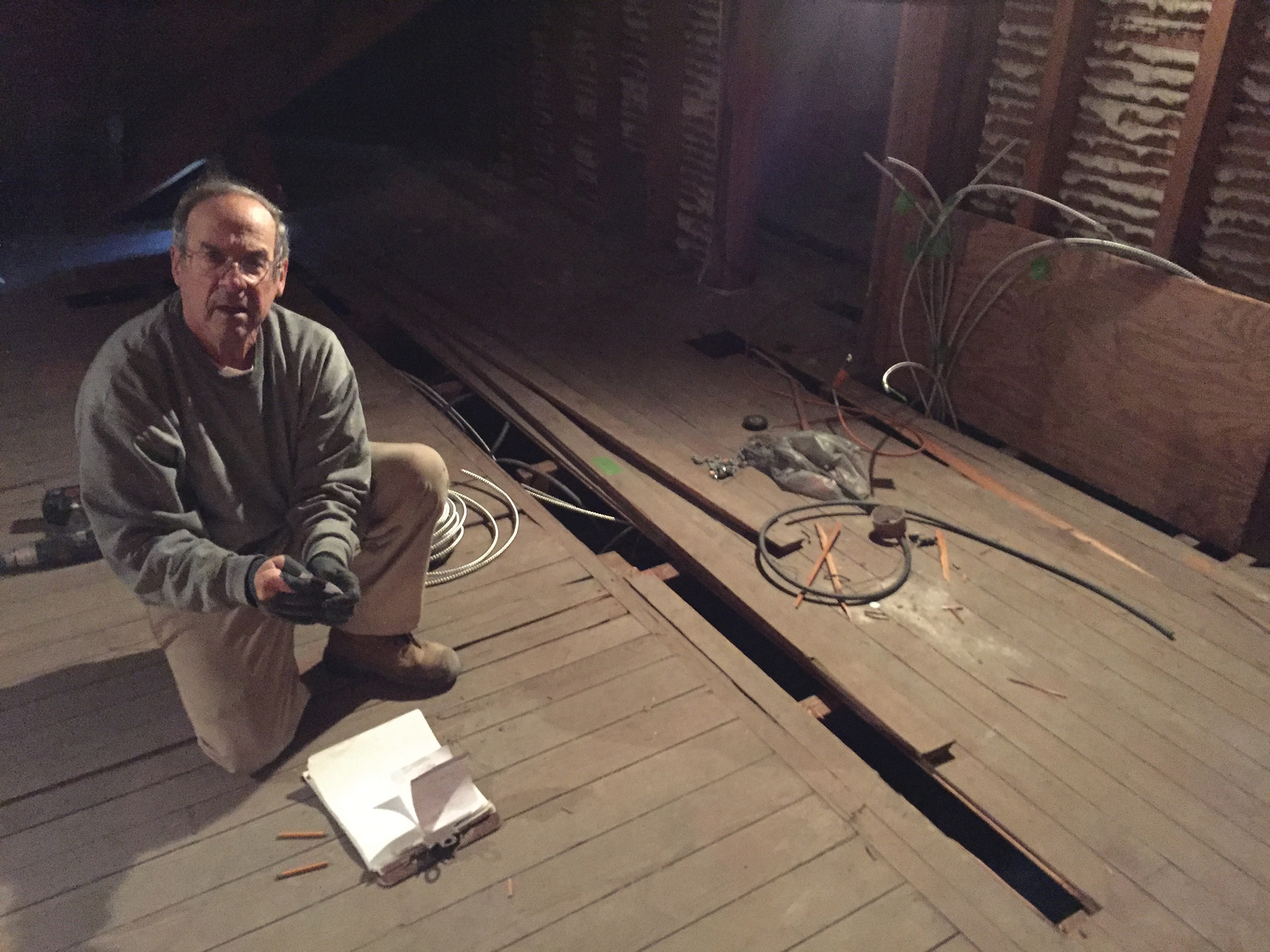

Little did he know the project would take up nearly two decades—and counting—of his life. Tennyson is part of a small group of volunteers who have faithfully devoted their time to fixing up Hollybourne Cottage, a grand old house in the National Historic Landmark District that was once the center of social life on Jekyll Island. Tennyson, now eighty, worked by himself for ten years before reinforcements arrived. “Dick is really the backbone of the whole thing,” says Don Watson, a seventy-six-year-old from Ontario who has worked on Hollybourne—helping to repair rotten shutters and flooring—for the past four years. “Without him, the house wouldn’t have lasted.”

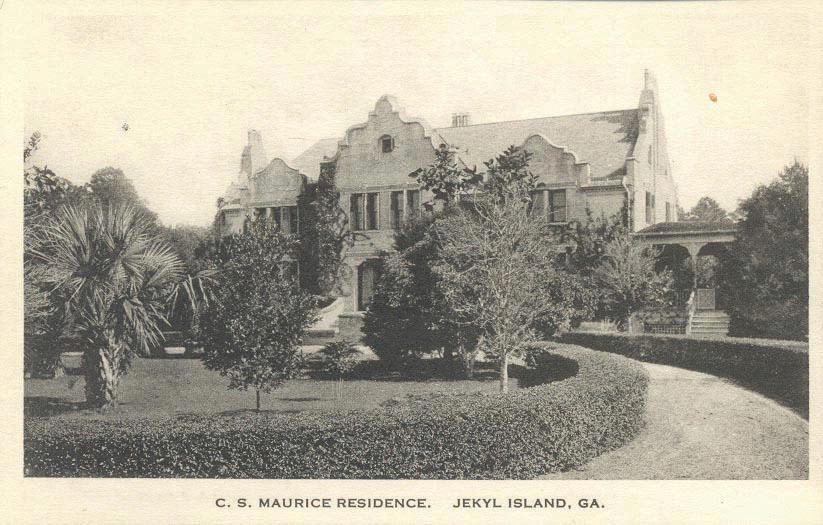

Built in 1890, the two-story, nine-bedroom property belonged to prominent bridge-builder Charles Stewart Maurice, a founding member of the Jekyll Island Club. According to June Hall McCash’s book The Jekyll Island Cottage Colony, it bears the distinction of being “the most interesting, architecturally speaking” of the island’s historic cottages. Built in the Jacobethan style, it was the only cottage of that era constructed with tabby, a concrete mixture traditionally made with lime, sand, and shell. The expansive 11,300-square-foot living space originally accommodated Maurice, his wife, Charlotte, and their nine children. Maurice brought his bridge-building experience into the design: In order to allow for large, open spaces on the ground floor without support beams to clutter the space, he used wooden trusses and long steel bolts to support the second floor.

The house became a gathering spot for members of the Jekyll Island Club. There were frequent teas and dinner parties. Charlotte, the ever-gracious hostess, was so attuned to the island’s social doings that she kept a menu diary of each dinner.

She died in 1909 in Pennsylvania of typhoid fever she contracted on the island. After Charles Maurice’s death in 1924, two of their daughters continued to enjoy the cottage every season until the state of Georgia bought the entire island in 1947 through eminent domain. The daughters, Marian and Margaret, were so bitter over losing Hollybourne that they not only never returned to the Georgia coast, they insisted on bypassing the entire state on their winter treks to Florida.

The coming years were not kind to what was once one of the island’s showcase cottages. The house remained empty and fell into disrepair, the victim of moisture, neglect, and weather. A full renovation was financially out of the question. In 1998, the Jekyll Island Authority commissioned the Getty Conservation Institute to conduct studies of the house, which resulted in a climate control system to keep further damage at bay. And that same year, Dick Tennyson went looking for his free golf game.

Tennyson, who had retired from GE a few years earlier, was already spending five months of the year on Jekyll. He always scheduled his winter exodus from New York so that he arrived on the island for a three o’clock tee time. “Back then I had a two handicap, and I was an avid golfer,” he recalls.

His first project was to restore the balustrade at the back door. Once he accomplished that, he was put to work on the shutters—all 116 of them. Rotten and misshapen, the shutters had taken the brunt of decades of weather. Each was either cleaned down to the heart pine and refurbished, or completely rebuilt. “For ten years I did nothing but restore shutters,” he says. He was an engineer, not a carpenter, and learned as he went. “My dad was always building stuff. I learned to do some things by watching him. I took to it naturally.”

After finally completing the shutters, he turned his attention to the foyer, which was covered with sheets of plywood so people could traverse the ruined floors with a degree of safety. On the side, he helped build new Habitat For Humanity homes, which is how he met Don Watson. “Dick was working on Hollybourne by himself, and I was afraid he was going to get hurt,” Watson says. A retired shop teacher, Watson brought a much-needed expertise to the project. “Anything I didn’t know how to do, I’d ask him,” says Tennyson.

Over the past few years, more and more volunteers have shown up—a couple of full-time residents, a handful of snowbirds, others who put in a week or two and never came back—and the work has taken on a faster pace. The renovation is far enough along for the house to be featured on island tours—as much for its unique preservation story as for its own sake. (Tennyson was a bit put off when he was told to leave some of the spaces unfinished to show the “before and after” of his efforts.) Time has even healed the rift with the Maurice family such that a descendant of Charles and Charlotte plans to get married at the house next year.

Tennyson points with pride to a visit a University of Florida architecture professor made last year. After a tour of Hollybourne, the professor informed a Jekyll Island Authority representative that the volunteers had completed hundreds of thousands of dollars of work. “Do you know what you have here?

What these guys have done is amazing,” said the professor.

It took the better part of two decades, but Tennyson’s efforts have earned him honorary luncheons from the Jekyll Island Authority and a handful of write-ups in the local press. But the recognition never mattered much, anyhow. “That’s the kind of guy he is. He has a real love for that house,” says Watson.

Next year, Tennyson plans to finish restoring the basement windows and electrical system; after that, he dreams of tackling a kitchen renovation. “How long am I going to work on the house?” he asks with a shrug. “How long am I going to live?”

Not-So-Haunted Hollybourne

The ghoulish rumors abound. Many believe the ghost of Margaret Maurice, the daughter of Hollybourne’s original owner, still inhabits the old mansion. There are stories about female footprints in the dust, of ghostly parties in the dark of night featuring a string quartet, of unusual cold spots. There are even tales that spirits have chased away those who endeavored to renovate the house.

Dick Tennyson has spent more time in Hollybourne than anyone alive. For the past eighteen years, he has worked inside the cottage, and he scoffs at the paranormal notions. “I’ve been there many days, many nights, and early in the morning and have never encountered a ghost. You’ll hear funny noises sometimes, but you can always correlate them to something. There are no ghosts.”