A ’70s-era seaside spectacle was submarined in part by budding environmentalists

By TONY REHAGEN

Beyond the famed Georgia Sea Turtle Center, where visitors meet convalescing turtles and learn all about them and other marine life, Jekyll Island features a thriving ecosystem renowned for its varied wildlife. Within a short walk from hotels all over the island, visitors can mingle with ghost crabs, alligators, plovers, banded water snakes, bobcats, and all manner of other fauna in their natural habitat. The rich biodiversity on Jekyll is the result of a conscious and organized effort by the island’s stewards to balance responsible development with historic preservation and conservation.

While the idea of featuring Jekyll as a natural wonderland in order to attract tourists is not new, public attitudes about the best way to show off that splendor have changed drastically through the years. In fact, there was a time, not long ago, when some locals believed that the best way to bring in vacationers and right the island’s economic affairs was to build a sprawling seaside spectacle in which some of Jekyll’s marine life would be paraded before onlookers in a permanent sea-life circus. Literally.

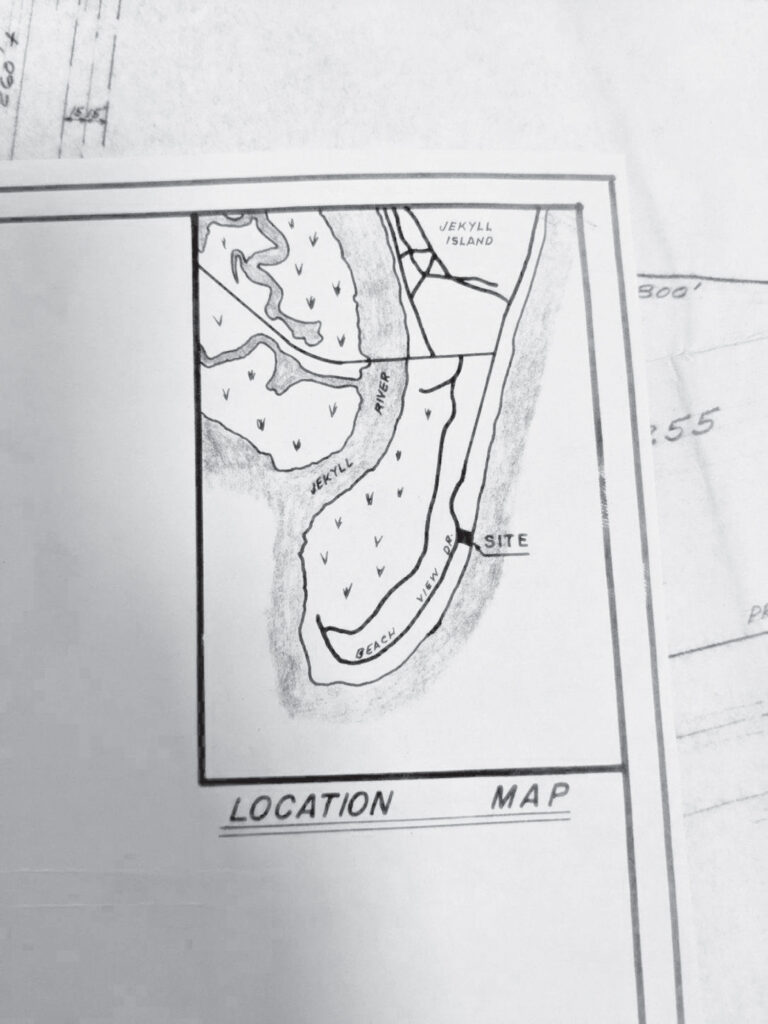

In 1970, a group of Brunswick residents formed a company called Marineland of Georgia (later changed to Sea Circus, Inc.) which was to develop a six-acre oceanside “superaquarium” to be built where the South Loop Trail now becomes Beachview Drive. According to backers, there were to be trained seals and trick-performing dolphins and penguins. Sharks and barracudas would swim in huge glass tanks. Horace G. Caldwell, executive director of the Jekyll Island State Park Authority from 1967 to 1972, told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine that the Sea Circus would be “clean recreation.”

The project, though, almost immediately ran into complications from within and without, including zoning issues and troubled finances. But it was more than bureaucracy and money that prevented the circus from coming to Jekyll. “This project was out of its time,” says Faith Plazarin, archivist and records manager at Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum. “It would’ve meant massive change for the beach environment, and some people weren’t pleased. It came at a time when our understanding of conservation was changing.”

Looking back, this sea-themed water park may have been more than a simple casualty of shifting moods. The Sea Circus might have served as the catalyst to rouse island passions and set Jekyll on its current conservation-conscious course.

In June 1972, with the proposed Sea Circus still in limbo, the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine published a cover story titled “Jekyll at the Crossroads.” The impetus of the article was then Gov. Jimmy Carter’s announcement that, starting on July 1, Jekyll would be responsible for paying its own operating expenses. To generate that sort of revenue, the island needed to lure tourists.

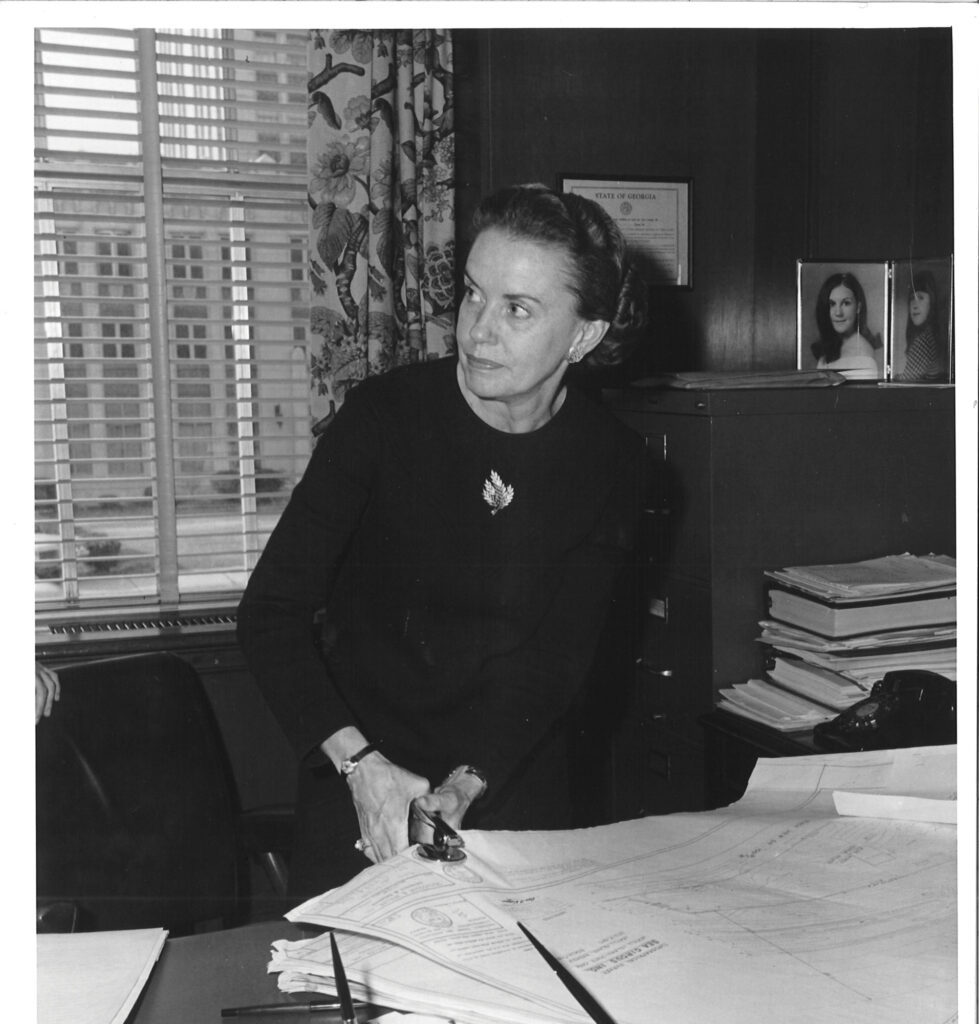

Authority board treasurer when the

Sea Circus was being considered.

At the same time, the JIA was working on a new land-use plan that would provide the layout for Jekyll’s future. A major question at the time: How much of the island’s natural beauty would be razed to make way for the concrete and steel of private development? The magazine mentioned the inland marsh that already had been turned into a public dump and the pit that provided dirt for new construction projects. These new projects already included two motels, an apartment complex … and the proposed Sea Circus.

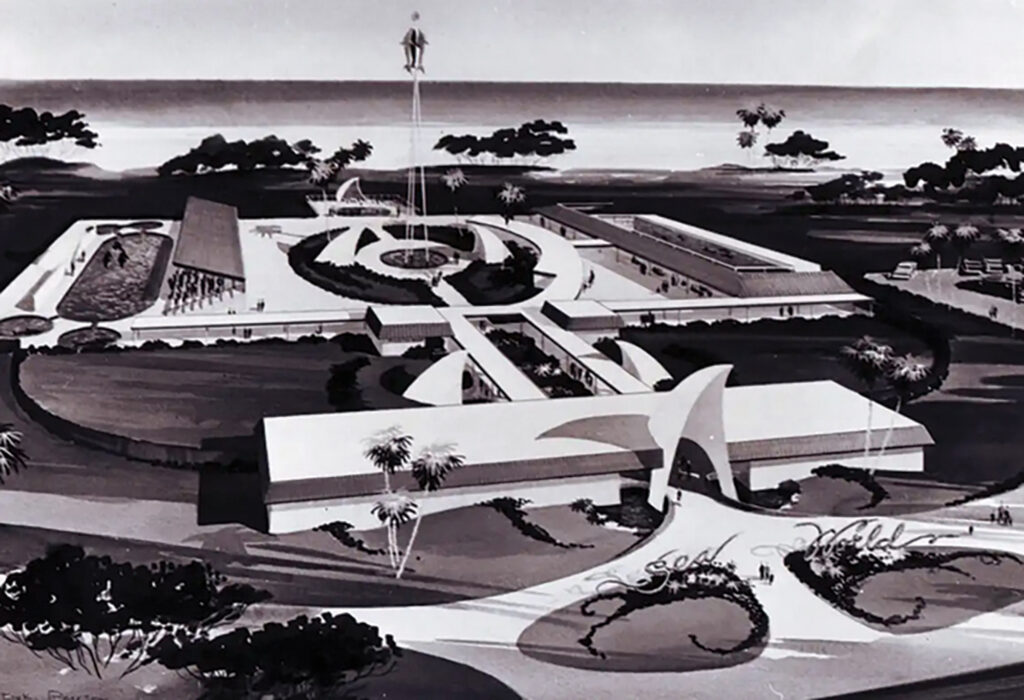

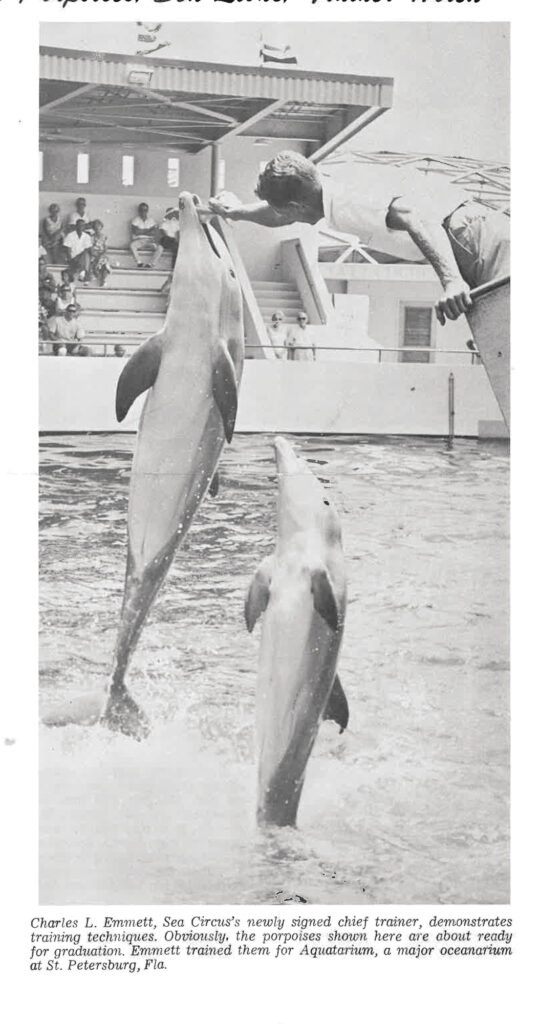

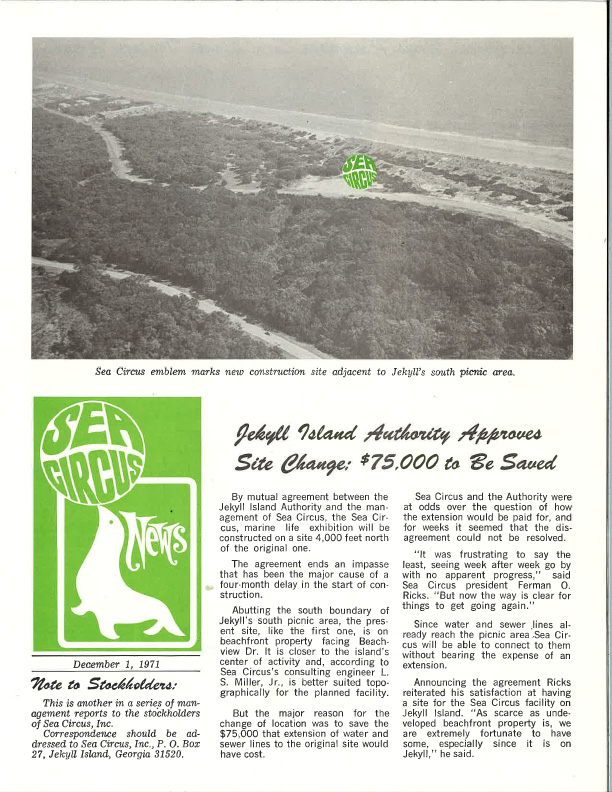

By the time the article hit newsstands, the Sea Circus was likely already doomed. It had been nearly two years since the Brunswick owners first announced their plans for the $750,000 project, which was to be publicly funded by a sale of stock (ads for stock in Sea Circus, Inc. put the price at $7.50 per share). Modeled after similar Florida parks—in St. Augustine (Marineland) and Miami (Sea Aquarium)—Jekyll Island’s Sea Circus sought to siphon off Northern travelers on their way south to the Sunshine State. The attraction would be a “living sea” exhibit, a “first of its kind in Georgia,” according to developers. Renderings produced by architects Schlosser & Miller of Brunswick portrayed a spacious modernist park with signature shark fin-shaped awnings and spires. Inside, more than 454,000 gallons of water, mostly in three primary tanks, would house marine life and be available for research scientists. Still, the focus was squarely on entertainment, not science.

The facility will overlook the ocean from a garden of subtropical flowers, shrubs, and trees, said one local newspaper at the time. Trained porpoises, sea lions, and possibly penguins will be featured in shows to be presented several times daily. An array of other marine life, from tropical fish to sharks, will be on view at all times.

In January 1971, the company (then known as Sea World, Inc.) declared it had secured the desired site on Beachview Drive, south of the former Stuckey’s Carriage Inn. “The site we have leased is one of the most valuable pieces of undeveloped oceanfront properties on the coast,” Ferman Ricks, president of Sea World, told the local press.

Developers weren’t the only people who understood the value of that beachfront real estate. Some of the people who live on the island, residents of this state park, have discovered ecology, reads the 1972 AJC article. They are demanding that marsh be saved and that habitat not be disturbed and that sand dunes be preserved and that not all of the rest of the beachfront go commercial.

The dunes were of particular concern. Archivist Plazarin points out that, at the time, Jekyll was still recovering from damage caused by 1964’s Hurricane Dora. Dunes were especially important in protecting the island against future storms, acting as a natural rampart against storm surges, waves, flooding, and coastal erosion. They also serve as a habitat for many species of wildlife. “There is no reason in the world the sea circus should be put on the sea,” E. Reeseman Fryer, Jekyll resident and president of the Coastal Georgia Audubon Society, told the AJC. “Those dunes are up to 26 feet [tall]. That’s the highest point on the island. They’re invaluable as protective barriers.”

Adding to the public furor was the fact that the Sea Circus site had not been designated for commercial development in the first place.

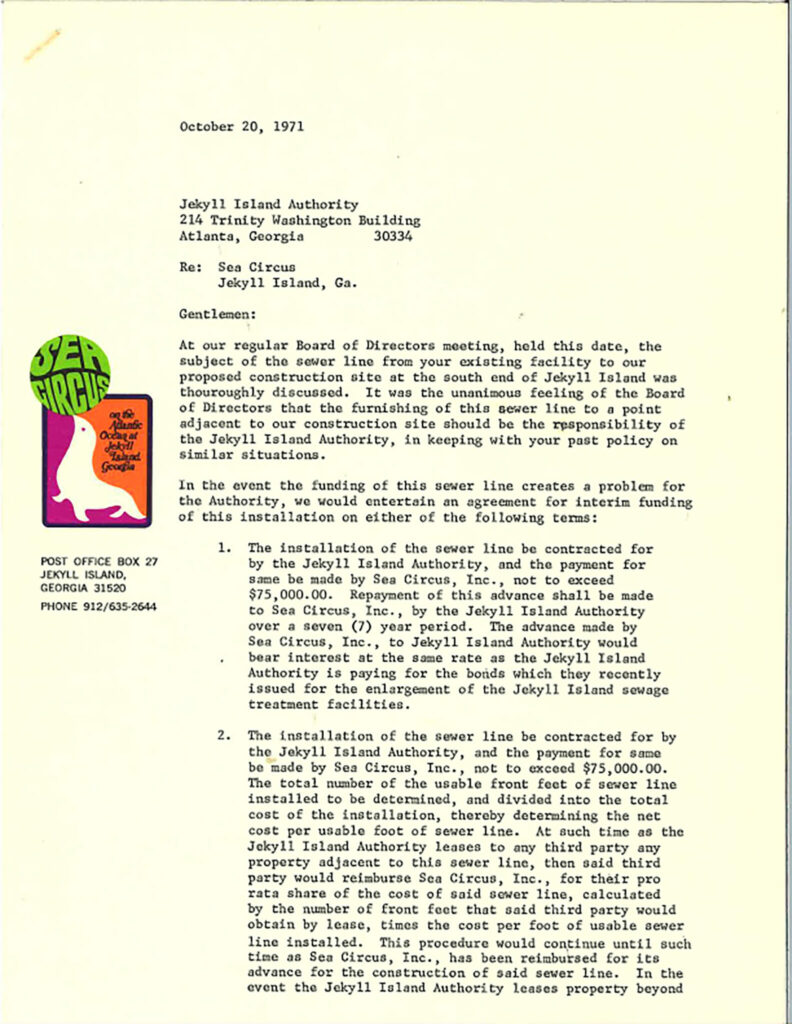

Despite the public protest, island and Sea Circus officials staged a ceremonial Sunday groundbreaking on the proposed site in June 1971. Two months later, they secured unanimous approval of the plans and building permits from the Jekyll Island State Park Authority (commonly known now as the Jekyll Island Authority, or JIA).

But not another shovel of sand or dirt was ever lifted for the project. According to minutes from subsequent JIA meetings, developers continually returned before the board with new financial backers. In February 1973, a representative reported that the company had secured permanent financing and planned to be under construction “within 15 to 30 days.” Two months later, they were back with another plan.

The last mention of the Sea Circus is in minutes from a September 1973 meeting, in which the Jekyll board said “a letter had gone out to Sea Circus, Inc. stating that the Authority could not approve their proposed method of financing.”

It’s difficult now to know just how much the increased public environmental consciousness of the 1960s and 1970s influenced the fizzling financial support of the project. But it’s clear that more than a few Jekyll residents and Georgia citizens realized what they had in the island’s natural bounty. And they weren’t about to give it up without a fight.

Whether this particular victory over unchecked development belonged to early environmentalists or not, the consequences of the failed project live on all over the island. Today, the South Dunes Beach Park sits near the one-time Sea Circus site. There, visitors can pack a lunch, stroll the boardwalk through scrub brush and trees, cross safely over 20-foot high sentinel dunes, and get a clear view of the beach, the sea, and the horizon beyond, without a fish tank or a penguin in sight.