A fascinating variety of Jekyll species rely on crypsis-or evolutionary camouflage-to thrive

By Josh Green

Photography by Jekyll Island Authority

Rest assured, the rattlesnake tucked just off the forested walking path, rendered virtually invisible by dapples of afternoon light and shadows, wants nothing to do with you. It yearns to be still and silent, to ambush the next rodent. You’re not a target for the rattlesnake and certainly not a meal—you’re a terrifying threat, the real apex organism. Its best defense against you is to be as invisible as a thick, five-foot-long Eastern diamondback rattlesnake can be. And on Jekyll Island, that defense almost always works.

Rarely seen and unbeknownst to most of Jekyll’s roughly 3 million annual visitors, a fascinating variety of island species have mastered crypsis. That’s a commonly used biology term referring to an organism’s ability to blend into its surroundings as camouflage from predators, or for ambushing unsuspecting prey. It’s the art of being there without being seen. How crypsis is achieved varies widely from the smallest, seemingly most susceptible island creatures (moths, for instance) to the largest and most naturally fearsome (yes, alligators). Even island plants such as mistletoe—it virtually disappears in the tree canopy until leaves start dropping in autumn—participate in the evolutionary hide-and-seek.

“With camouflage, a lot of people think of snipers and the military. These species are essentially doing the same thing, including ambush predators that want a meal,” says Joseph Colbert, Jekyll Island Authority wildlife biologist. “There’s a lot of stuff that we as biologists see regularly that some people are only fortunate to see on rare occasions.”

Wildlife camouflage can entail more than color patterns, such as changes in animal behavior or tactics to mask scent. Collectively, it’s a primary reason why sticking to permitted beach areas and designated nature trails while exploring the wilds of Jekyll is beneficial for both visitors and the animal kingdom.

STEALTHY SNAKES

Almost invisible in forest foliage, Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes are among the highest priorities in Jekyll conservation. They’re genetically and characteristically distinct from their mainland cousins, meaning they’re wholly dependent on the island’s internal snake population. (Fear not: No rattlesnake bite on a human has ever been recorded on Jekyll, and only a handful of sightings are logged per year.) These snakes aren’t fans of swimming, so they typically remain on the island for life, perpetually in hiding.

Michael Brennan, a PhD Student at the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, has been monitoring and tracking Jekyll’s rattlesnake population with tiny Bluetooth and radio transmitters for several years. To date, 63 adult rattlesnakes have been found in three distinct home ranges: upland marshes, dune systems, and maritime forests. A “barometer” or “umbrella” species at the top of the food chain, like rattlesnakes, can use crypsis to stay undetected and thrive; when the umbrella species is thriving, it benefits the rest of the animals in the habitat by keeping things in check. Rattlesnakes’ dark-light diamond patterns are extremely effective camouflage, but only in the right places, with the proper cover. Evidence also suggests they’ve evolved to become smaller. Eight-foot individual rattlesnakes used to be common, but due to various threats over generations, the species evolved into a reduced size. Today, the largest individuals rarely reach six feet in the wild. There are instances, however, when crypsis backfires for rattlesnakes.

“With behavioral crypsis, a rattlesnake’s natural tendency is to freeze, even when they’re not in ideal habitat, like when they’re crossing a road,” Brennan says. This can sometimes lead to fatal encounters with vehicles. “Their pattern works best when they’re not moving and fully exposed on a surface like a road.”

Rattlesnakes aren’t alone in their reliance on crypsis across Jekyll. Venomous brethren cottonmouths have a pixelated scale pattern that helps them blend into wetlands and grassy woodland edges. Rough green snakes, a skinny nonvenomous species, exhibit movement crypsis by rocking back and forth in trees to mimic wind-blown vines. Coachwhips are adept at disguising themselves in dry, sandy dune areas. And corn snakes, with darker orange and brown colorations, “blend in remarkably well with pine straw,” says Brennan. “You’d be amazed how frequently people will walk right by a snake sitting on the edge of a trail—dozens of people—and have no idea.”

Those natural settings, as Colbert stresses, don’t always maintain themselves. “Providing [snakes with] the right habitat with lots of cover is one of the things we aim to do,” says Colbert. “And if we’re suiting their needs, we’re suiting a lot of species’ needs.”

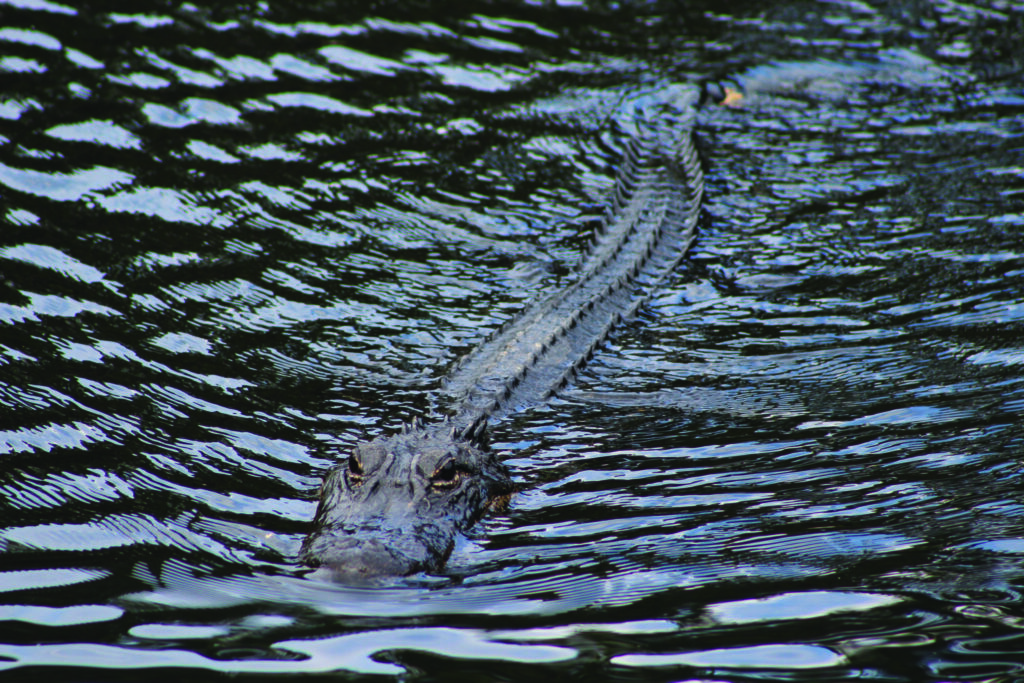

SLY GATORS, BOBCATS, AND DEER

Crypsis is one of the most widely employed biological phenomena used by wildlife. That log near the banks of a pond could be an alligator mimicking a fallen branch, ready to sneak up on prey. Biologist Colbert notes that gators in Florida have even been observed resting on the surface with sticks on their snouts to lure in birds building nests.

Bobcats are another alpha species that commonly hide in plain sight. With spotted and striped fur that mimics blades of grass, sticks, and twigs, bobcats are patient, creeping hunters capable of sitting still for long periods before pouncing on rabbits, squirrels, and other rodents, and sometimes smaller deer. About a dozen adult bobcats have been found on Jekyll to date. “They kind of prowl and are hard to see, like how a cat moves in tall grass with just its eyes sticking out,” says Colbert. “People don’t see them often on the island unless they’re quiet.”

Fawns are also capable of mime-like stillness when threatened. Crypsis is effective when combined with spots that lend the appearance from a distance of sun and shade mixed, but it’s not the deer’s only self-preservation tool. They also have scent crypsis. “If a fawn doesn’t want a coyote to smell it very easily, they won’t put off much of a scent and can mask it,” says Colbert.

CRAFTY SMALLER SPECIES

Practically any habitat on the island is populated with members of the insect kingdom that employ crypsis. Stick bugs are self-explanatory, and some beetles can pass for little stones. A few moth species are easily mistaken for rolled-up leaves on the ground. In the amphibian world, leopard frogs’ brilliant greens and other colors are blatant on a sidewalk, but at the edge of a wetland, the animals all but disappear.

Nighthawks and shorebirds such as Wilson’s plovers tend to sit on their nests in dunes, relying on camouflage until beachgoers are practically on top of them. Their spotted eggs, even on close inspection, can look exactly like sand. “We look for their eggs, which sit in a shallow bowl-shaped nest that has footprints leading to it,” says Colbert. “The footprints we follow to track them can’t be found on rainy days.”

Wildlife camouflage on Jekyll extends offshore as well. Hermit crabs are often mistaken for common shells until those shells start trying to crawl out of kids’ buckets. Some tiny jellyfish are almost invisible in the shallows, and at the seafloor, stingrays and flounder use the darker top portions of their bodies to blend into sand, masking themselves from predators above. Other crabs, snails, and turtles use epibiosis, or the process of letting smaller organisms such as barnacles grow on their shells, as a means of disguise.

No matter their size, species across Jekyll rely on human intervention to help crypsis work, whether through habitat restoration or the creation of microhabitats that dot the island. “I created a stick pile, and we found a king snake in it three days later, perusing underneath it,” says Colbert of one recent example. “We were happy about that.”