How America’s Super Rich Learned to Party on Jekyll

By MARY LOGAN BIKOFF Photos Courtesy of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum

When the monied members of America’s high society arrived at the Jekyll Island Club in its early years, in the late 1880s, they came—much as visitors do today—for relaxation, pleasant climes, and merriment. But while they sought simple pleasures, their social diversions were often a bit more elaborate than throwing a blanket on the beach.

This was the Gilded Age, a time of an explosion of industries—railroads, steel, and oil among them—that created a new social class with breathtakingly lavish lifestyles. It is said that the uber-exclusive Jekyll Island Club member list, which included names like Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Pulitzer, and Astor, comprised one-sixth of the world’s wealth at one time. These industrialists and their families—American royalty—fled from their extravagant homes in the wintry urban north for the easy gentility of the island, where they sunned, yachted, rode horseback, hunted in the wild pine forests and, yes, threw many a festive event that defined an era like no other.

Frequent gatherings, from banquet-style picnics on the beach to stately dinner dances at the Club, were the order of the day. Costume parties, dinners for dozens aboard opulent yachts, balls with ragtime music, swinging Big Band dances, genteel afternoon teas, and lawn tournaments on immaculate grounds were among the amusements. No expense was spared.

Still, the upper-upper-crust families who wintered on Jekyll considered their time at the resort to be quite simple and rustic, compared to the over-the-top grandeur of their summer homes in ritzy locales like Newport, Rhode Island. On Jekyll, Spanish moss–draped live oaks and shell roads took the place of manicured acres and imposing gates.

“They viewed Jekyll as a place where they could let down their hair,” says June Hall McCash, author of The Jekyll Island Cottage Colony. “They still dressed to the nines, but they really believed they were living their simple lives there. “What was considered rustic by Gilded Age millionaires would be deemed outlandish by most others.

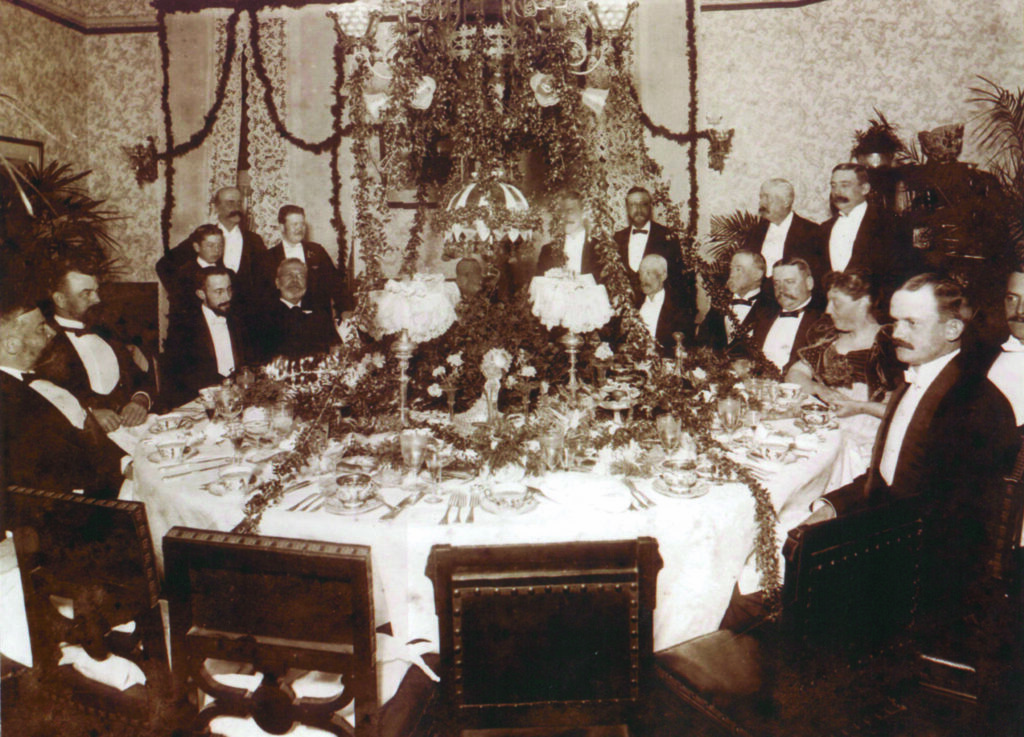

McCash notes the vacationers packed enormous wardrobes for the season. Women donned a different gown to dinner each night, while men turned out in tuxedos. Formal dinner dances at the turreted Victorian clubhouse, filled with mahogany and wicker furniture and custom rugs, were common. Tables teemed with engraved silver, crystal, imported china, cut florals, garlands, and palm fronds. Historical menus from the era reveal bountiful, indulgent dinners featuring sardine canapes, diamondback terrapin, fresh local oysters, and desserts like English plum pudding with brandy and baked bananas au Jamaica. The club’s fishermen hauled in local seafood each day for dishes like shrimp salad and crab ravigote. Butter was imported from Tennessee. The best chefs were brought down from New York restaurants for the winter, and some members were served by personal waiters.

According to The New York Times, one such dinner party hosted by Mrs. T.W. Pearsall in 1889 was notable for its extravagant party favors, which included typical trinkets like cards and candy but, for a few lucky guests, a horse and cart, a dog and gun, an alligator… and even a yacht.

Less formal were the frequent picnics on the beach, though those required a great deal of orchestration, too, mostly by the family’s large arsenal of personal servants and employees of the club. (Staff outnumbered the guests.) Old photographs show long wooden tables set up with ice buckets stocked with wine, and women lounging under parasols in voluminous hats overflowing with trim, plumes, and flowers, wearing gloves up to their elbows. Multi-course meals were served, and beach diversions arranged.

Marian Maurice, the daughter of prominent bridge builder Charles Stewart Maurice and Charlotte Maurice of Pennsylvania, who often hosted festivities in the magnificent Jacobean cottage Hollybourne, wrote to her grandmother of one such oyster roast on the beach in 1898: “After lunch, we danced a Virginia Reel in which all, old and young, took part, one of the gentlemen being 89 years old, others of them children only 8. It was very jolly.”

According to Andrea Marroquin, curator of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum, other amusements on the beach included races, games, and athletic tournaments called gymkhanas. In the 1920s, open-air dune buggies known as redbugs arrived. Members used them to bounce around the island, and races on the hard-packed sand beaches became a favorite activity.

The club register recorded the many comings and goings of guests, who arrived to visit and also became part of the festivities, many of which took place at the private cottages. Fine rugs and wicker furniture were dragged out to the lawn for tea, games, and sunshine. Frances Baker held an inaugural tea for the 1893 season that was attended by the whole island at her gracious Solterra, which a New York Times story declared “was handsomely decorated with azaleas, hyacinths, ferns, and palms.”

A member’s daughter, Bettie Huidekoper, recalled a party in the 1930s celebrating the club’s founding.

After a “glorious dinner celebration under a vast tent, with several long tables set with a solid line of pink and white camellias down the center,” the teenagers strolled and biked down the shell road in evening dress dancing under the moonlight to music from a “new-fangled battery-operated radio.” Huidekoper called them the “happy kids of the Big Band era,” and reminisced dancing the two-step to the likes of Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Glenn Miller. “We danced until the battery died,” she says.

Other occasions to throw a party (though it didn’t take much to prompt a celebration) included Washington’s and Lincoln’s birthdays. These called for formal dinners where chefs rolled out the likes of Uncle Sam pudding sauce, braised sweetbreads à l’independence, and Martha Washington pie.

Parties for staff, too, an English tradition, became customary during the early years (at least for the white staff on the still-segregated island). One St. Patrick’s Day in 1889, the same year Mrs. T.W. Pearsall gifted a yacht as a party favor, she hosted an elegant ball at the clubhouse for club staff members. After an opening dance between club members and employees, the members retired and the employees danced until an elaborate supper at midnight.

And of course, there were holiday parties. Many families came down for the season before Christmas, even as early as Thanksgiving. Christmas on the island was recorded by Munsey’s Magazine in 1904: “Each winter the club opens for a Christmas Dinner, and the members come and go until warm weather drives them away toward the end of April.” Other holiday festivities were more understated. Cornelia Maurice of Hollybourne Cottage recounted the Christmas of 1898 in a letter to her grandmother. Their custom was to include the club’s superintendent, head housekeeper, and boat captain at Christmas dinner. That year, Maurice wrote: “We arranged a small tree in the centre of the table and around it a present for each one with a ribbon attached to it, and the pile in the centre about the tree covered with holly. When dinner was over, each one pulled the ribbon nearest them and out came their presents from their hiding places. It caused a good deal of surprise and fun.” In 1901, the Maurice family, who entertained almost daily, threw a Christmas party for the 17 children of the club staff, from six months to 11 years old, who consumed “large quantities of ice cream and cake.”

The annual holiday costume balls thrown in the Roaring Twenties by the Jennings family of Standard Oil were legendary. Themes were often inspired by garments they picked up on their travels abroad, from Chinese silks to Marie Antoinette–style garb.

“Reflecting their ability to travel, costumes often celebrated other cultures or nationalities,” says Marroquin.

“Partygoers also frequently dressed as famous historical figures. For one party, Constance Jennings wore a lovely ball gown designed by a New York costumier. It was a lavender brocade and gold lace dress from the time of Louis XVI with the appropriate towering white wig.

“Then, as now, partygoers also dressed up as popular celebrities or personal heroes. Jeannette and Constance Jennings dressed as the Gish sisters—two silent screen starlets,” Marroquin adds. “Then Jeannette changed clothes to dress up as another hero—her father Walter Jennings, who was a Standard Oil Company executive.”

“Then, as now, partygoers also dressed up as popular celebrities or personal heroes. Jeannette and Constance Jennings dressed as the Gish sisters—two silent screen starlets,” Marroquin adds. “Then Jeannette changed clothes to dress up as another hero—her father Walter Jennings, who was a Standard Oil Company executive.”

Some of these costumes, including the Louis XVI dress, can be viewed today at Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum. (The donor of that costume wrote: “I enclose the dress. The wig ‘died’ as we kids played with it until extinction.”) They are among the vestiges of a time when some of the world’s richest people celebrated their wealth on an otherwise quiet Georgia island.