Soldier, farmer, brewmaster, William Horton shaped Jekyll.

By Nicole Letts

Illustrations by Michael Frith

On the north end of Jekyll Island, just off of Riverview Drive, tucked up against the edge of a dense maritime forest, stand the ruins of what once was the home of one of the island’s most influential leaders. Though he’s not nearly as well-known as his friend and superior, Gen. James Oglethorpe—the founder of the colony of Georgia—or the many industrialists who more than a century later used the island as a sort of playground for the wealthy, Maj. William Horton made a mark on the island that is unmistakable.

A Georgia version of Thomas Jefferson, Horton used his many talents to tame the often unforgiving conditions of early colonial life on the island. A soldier, a statesman, a farmer, a builder, and the first person to brew beer in the colony (something that proved especially useful at the time), Horton played a critical role on Jekyll in the early 18th century.

Born in 1708 in Herefordshire, England, Horton attended what is known today as Abingdon School, one of the oldest independent schools in the United Kingdom. While historians are unsure of many details of his young adult life, they know that Horton left England in October of 1735 and arrived in colonial Georgia on February 6, 1736, aboard Oglethorpe’s ship the Symond, when he was just 27 years old.

The curator at Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum, Andrea Marroquin, explains how Horton quickly climbed the ranks to become an important figure in the shaping of the island: “He seems to have been a civilian when he came over,” or a low-ranking officer, she says. “He is referred to as Mr. Horton, but he ultimately joined the regiment to become major.” In fact, only a few months after Horton arrived in Georgia, Oglethorpe dispatched him to St. Augustine, Florida as an ambassador to meet the Spanish governor.

Coastal Guardian

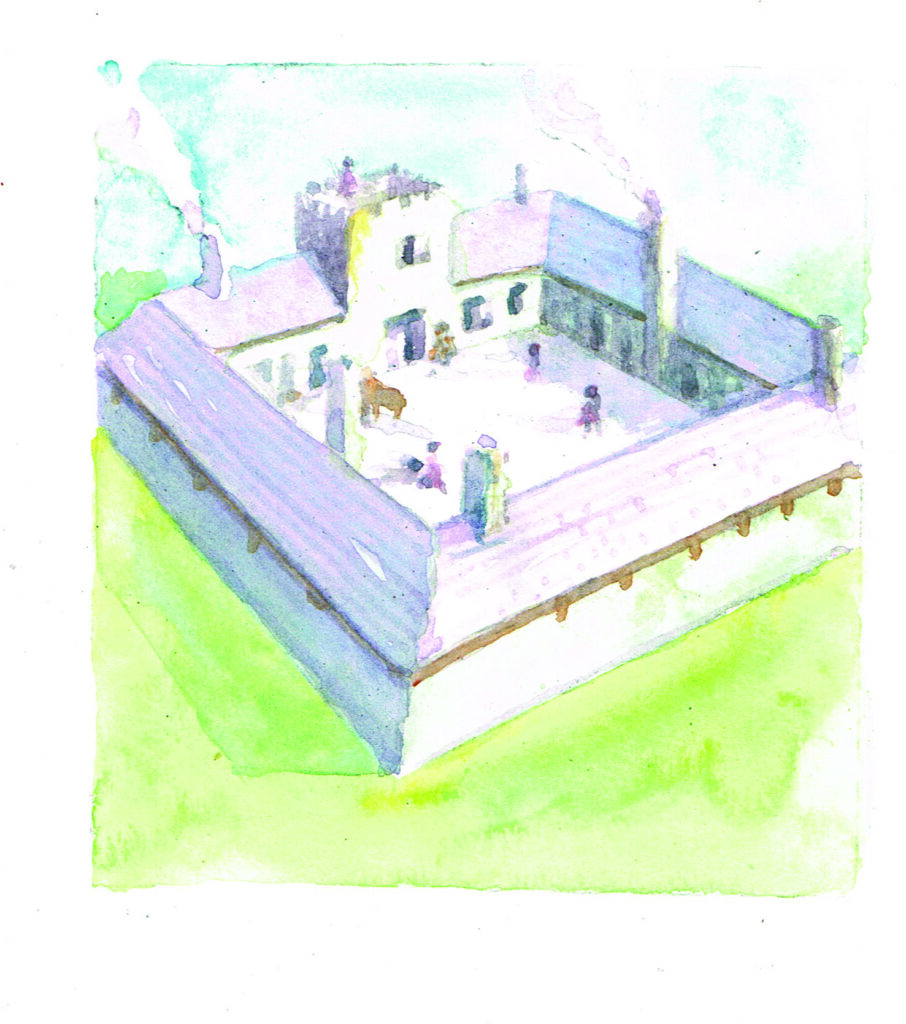

At its inception in 1732, Georgia was an important British foothold, serving as a buffer between Spanish-ruled Florida and the British Carolinas. Jekyll Island was established as a military outpost to protect St. Simons Island to the north and its coveted Fort Frederica.

Oglethorpe recognized the importance of the location near the southern border of the colony and needed a respected individual to help build and run the fort in his absence. To fill that role, he turned to Horton, who became the military commander overseeing the fort and the militia. “Because Fort Frederica and Jekyll were strategic locations for the British,” says Marroquin, “Horton had a prominent role in the diplomacy and the interactions between the English and Spanish.”

Not unlike Virginia’s Jefferson, known for his affection for and diplomacy in France, Marroquin describes Horton as not only well-respected by Oglethorpe and the Spanish but well-liked among many of his constituents. “Accounts we have say he didn’t bathe for weeks because he chose to give up his own tent at the Fort to be used as shelter for the sick,” she says. Additionally, he’s credited with giving his own cattle and corn supplies to soldiers to help sustain them.

A Renaissance Man

Colonial life in America came with harsh conditions for which few were prepared. Horton, however, seemed to thrive in the challenging environment. Even without a background in agriculture (he was once employed as an undersheriff, a law enforcement officer who serves as second-in-command), Horton demonstrated a clear knack for farming, similar to Jefferson and his well-known passion for horticulture.

Horton’s natural talents enabled him to successfully grow crops and raise livestock for the fledgling island and its military. With the labor of 10 indentured servants, he grew traditional Southern crops such as indigo and cotton, sustained cattle and sheep, and harvested corn and barley, the latter being particularly useful and important for another creative endeavor: brewing beer.

Horton is credited with establishing the first brewery in Georgia. According to Marroquin, that was particularly significant for a couple reasons. Coastal areas are inherently more susceptible to waterborne illnesses due to the proximity of the ocean and other freshwater sources, and early settlements lacked proper sanitation systems, so sewage and waste often ended up in the waterways. Having an alternative to drinking water—say, freshly brewed beer—helped prevent disease.

Marroquin says that the beer had another use: “It helped to create unity in the colonies. When there were misunderstandings amongst people, Horton would provide them with beer, telling them to drink and make friends [instead of arguing].” Even in that endeavor, Horton mirrors Jefferson, who is credited with bringing wine to the colony of Virginia, an industry that thrives in the state to this day.

The Horton Homestead

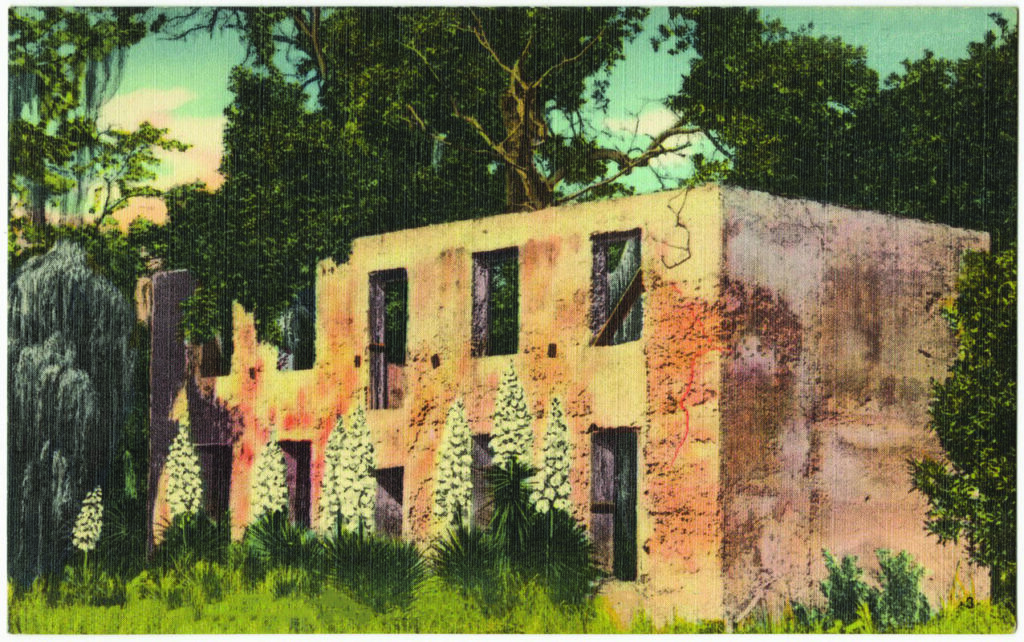

Horton originally built a two-story wooden structure for his family in 1736, though that home was destroyed after 1742’s Battle of Bloody Marsh on St. Simons as the Spanish retreated. Undeterred, in 1743 Horton built a home for himself, his wife, and his two sons. That structure is now known as Horton House, the remains of which still stand off Riverview Drive on the north side of the island.

The house was constructed of tabby, a type of concrete made from a combination of oyster shells, sand, lime, and water. Tabby was widely used in coastal communities because of the abundance of its raw materials and its strength. Horton House, one of the earliest examples of a tabby structure in the state, is now part of the National Register of Historic Places, along with an outbuilding on the same property.

After a long illness, Horton died in Savannah in 1748. His wife, Rebecca, never remarried, receiving a widow’s pension until her death in 1800. Horton’s land grant on Jekyll passed to his son, Thomas, who eventually abandoned the property. Thomas later was a representative in Georgia’s constitutional convention in 1788.

Amid the rugged landscape of Jekyll Island and the shifting political tides of colonial Georgia, Maj. William Horton balanced the complexities of diplomacy and military duty with the challenges of daily survival. He stood as a testament to both leadership and innovation, traits that helped shape the island that we know today.