New archaeological surveys yield tantalizing clues into island history.

By JOSH GREEN

When Tropical Storm Debby whipped into the East Coast in August of 2024, Jekyll Island largely escaped its wrath. But the wind, water, and subsequent erosion that it wrought exposed some mysterious bones, peeking out of ancient mudflats on Jekyll’s northern end. The bones were relatively large. Were they human?

The Jekyll Island Authority (JIA) reached out to archaeology teams at the University of North Georgia and other academics, and soon paleontologists specializing in mammals were en route to the island. What the storm had uncovered, researchers soon found, was the full skeleton of a horse, down to its teeth. After partnering with University of Georgia radiocarbon dating experts, JIA officials learned that the bones date to 1740—give or take a decade—and could be historically significant enough to earn a place in Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum. The horse, after all, is older than the Declaration of Independence.

“It’s really neat because [the bones’ age] puts us back into the Colonial Era of Maj. William Horton’s short stint on the island,” says Will Wagner, JIA’s director of historic resources. “The horse could have belonged to him.”

For decades, painstaking excavations (performed by archaeologists, not Mother Nature) have been peeling back Jekyll’s layers to unearth troves of artifacts, bones, and other objects, lending insight into who’s inhabited the island across the centuries and how they lived. Formal archaeological work on the island dates to surveys in the 1950s. Forty years later, researchers from the University of West Georgia found widespread Native American middens (mounds of oyster and mollusk shells) that exposed the eating habits of the island’s Mocama and Guale tribes. Before the construction of Jekyll’s Beach Village a decade and a half ago, more archaeological consultations were completed, as state and federal laws require. Still more were done before the remodeling of Pine Lakes Golf Course in 2023.

Each archaeological survey must be done in a way that supports JIA’s core mission: to preserve the island’s history and its natural state. Only 35 percent of the state-owned island, by law, can be developed, so each carefully considered construction project must be accomplished inside a strict footprint. Archaeological surveys ensure that construction won’t damage or disturb any links to the past that might be of incalculable social or environmental importance.

A recent large-scale project at Jekyll’s original golf course is particularly significant.

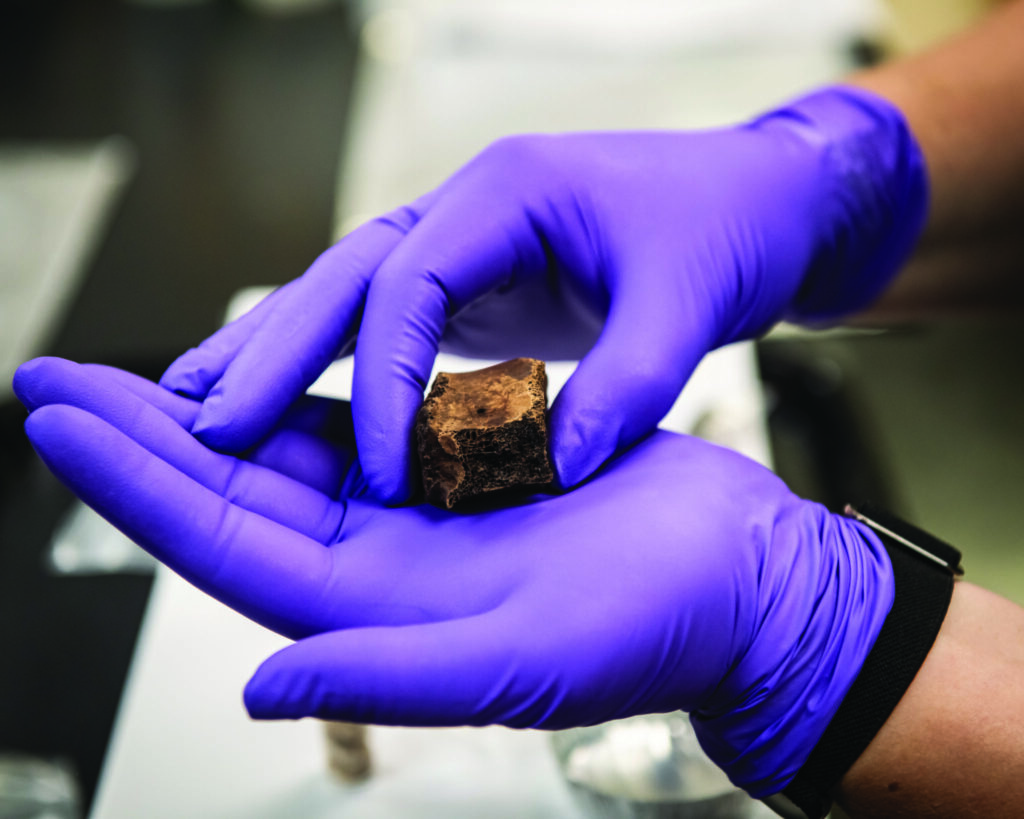

Carla S. Hadden, Ph.D., works to date the unearthed bones at the UGA Center for Applied Isotope Studies.

As glimpses into bygone societies go, the ongoing restoration and expansion of the oceanside Great Dunes Golf Course has been extraordinarily fruitful. The historic 9-hole course, built by famed designer Walter Travis between 1926 and 1928, is being remade to restore the original layout, with help from historic aerial and ground photos that show the former positioning of greens, bunkers, and other features. (Nine holes at neighboring Oleander Golf Course also are being repurposed to make Great Dunes an 18-hole course, while most of the rest of Oleander will become a wildlife refuge.) Back in 2008, long before the Great Dunes’ restoration kicked off in October of 2024, JIA hired archaeologists from Brockington and Associates in Savannah to conduct an initial survey of the previously developed land. That was Phase 1, and in Georgia, it typically entails digging small holes with shovels, in this instance, every 50 feet or so. Then, archaeologists sift through the soil to locate and identify archaeological sites within a project area and determine site boundaries. That preliminary work, in Great Dunes’ case, yielded a substantial haul: 246 artifacts (technically, that’s any object at least 50 years old made or modified by humans), including pottery and stone tools. They were accompanied by faunal remains; a lot of deer, fish, turtle, and even bobcat bone.

“It gives you a good idea of what [people of the time] were doing in that area, what they were eating, and how they were responding to their environment,” says Becca Stewart, a Brockington and Associates archaeologist.

More than a decade later, in the fall of 2024, Stewart was called back to Great Dunes to monitor construction and collect and document archaeological findings as the golf course restoration began. That dance, between building and preserving, is a delicate one. While trenches and bunkers were being excavated with backhoes, Stewart operated with shovels, trowels, and screens with quarter-inch mesh to sift out artifacts, then logged the depths of discoveries to ensure the “vertical integrity” of the finds (the oldest being the deepest). Stewart worked with the course architects overseeing the redesign, Jeffrey Stein and Brian Ross, to modify the shape of some sand traps to preserve middens, and to make sure that irrigation pipes and sprinkler heads didn’t disturb other culturally significant spots.

“The goal in archaeology is not to dig up every square inch,” Stewart says. “It’s really to preserve as much as we can in place.”

For security reasons, exactly where the site is on the links isn’t readily available information, but it’s quite large as coastal sites go: roughly 300 meters by 150 meters, large enough to likely have been a settlement of some sort, hidden just beneath the surface for decades.

“With it being that large, there’s a couple of ways you can interpret it,” says Alex Sweeney, Brockington’s senior archaeologist and vice president. “Is it possibly part of a village? Or could it be basically a series of short-term encampments that could have been occupied over and over again through different seasons?”

Lab analysis indicates that ceramics on the site date from the Early/Middle Woodland period (1000 BC to AD 750) to the Mississippian (1000 to 1600 AD, or right at the brink of European contact). Elsewhere, shell middens were found under just three inches of turf and soil. Deeper excavations revealed potential hearths and pits, suggesting the site could have been a ceremonial or feasting area, with quick access to the ocean.

Exactly how much material was collected at the Great Dunes site is still being quantified by Stewart’s lab partners, but highlights included “some really big pieces of pottery that were gorgeous [with] this rectilinear, complicated stamping on it,” she says. Overall, the site is significant.

JIA’s Andrea Marroquin, Mosaic’s curator and an archaeologist herself, said the first step is to determine exactly when, how, and by whom the artifacts were being used, and then use them to help educate Jekyll visitors today. The legally required archaeology work isn’t inexpensive, but Marroquin calls it the cost of doing business when that business is historic preservation. “We’re hoping to use those materials,” says Marroquin, “to create new and better interpretations for the museum and other spaces around the island.”

Beyond the links, it’s impossible to say how many relics of bygone societies lay beneath Jekyll’s protected lands. But every found object adds to the island’s story, a story that belongs to the public.

“People don’t think about it, but there’s actually a ton of information in the ground, and not all of it’s been explored yet,” says Stewart. “It’s interesting to see how often archaeology is underneath your feet but you just don’t realize it.”

The Big Digs

Historical milestones in Jekyll archaeology.

Late 1800s:

Historians credit the island’s Club Era with laying the groundwork for stewardship efforts that include archaeology today, though wealthy inhabitants were more concerned with preserving architecture and historic ruins than vestiges of prehistoric civilizations.

1950s:

Cursory archaeological work takes place as a means of surveying the island overall, though no good records of that research survive.

1966:

This island’s first major excavations, as led by prominent archaeologist Charles Fairbanks and others, focus on and around the 1743 historic Horton House site.

1980s-1990s:

Extensive fieldwork led by late University of West Georgia anthropologist Morgan Ray Crook succeeds in identifying a variety of prehistoric and historic sites around the island.

2008:

Initial survey of Great Dunes Golf Course completed.

2008-2010:

Before development (and any ground-disturbing activity), the section of the island that will become the Beach Village is thoroughly surveyed by archaeologists.

2024:

Tropical Storm Debby partially uncovers horse bones that date to around 1740, possibly a new link to historical local agriculture practices.