Inside the ongoing mission to protect and rehabilitate Jekyll’s diamondback terrapins.

By Lauren Finney Harden

Photography by Allison Leotis

On any given day from April to July, visitors driving the long, flat causeway that leads to Jekyll Island might be confronted with bright, flashing traffic signals. They’re not to point out speed bumps or the occasional bicyclist. They’re not there to re-direct beach-goers. The heads-up is designed instead to alert drivers to female diamondback terrapins crossing the road. That’s just one of a number of steps that the Jekyll Island Authority’s Georgia Sea Turtle Center is taking to protect the native turtle population.

“Our mission,” says Michelle Kaylor, director of the Center, a wildlife hospital and rehabilitation center founded in 2007 by Dr. Terry Norton, “is preserving, maintaining, managing, and restoring the natural communities and species on Jekyll Island.

FERTILE TURTLES

While the Georgia Sea Turtle Center’s focus, as its name spells out, is on sea turtles, the Center attends to several turtle species in its work, including the native diamondback terrapin.

A quick primer: The diamondback terrapin is the only turtle that lives in brackish water, where salt water from the ocean meets fresh water from the mainland. Native to North America, the turtles can be found all along the East Coast and in parts of Texas. The diamondback terrapin has seven subspecies, differentiated by their physical characteristics and the habitats in which they live. The most prominent subspecies around Jekyll Island, the most recognizable, is the Carolina diamondback terrapin.

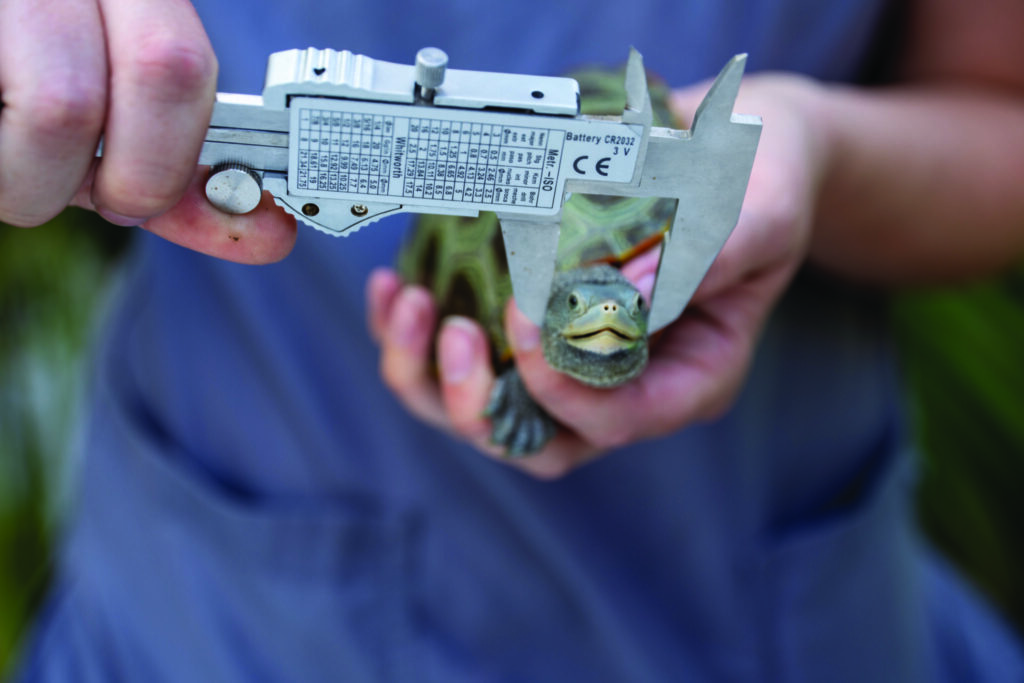

The female Carolina diamondback terrapin can grow to about a foot long. Males grow to about five to six inches long. Their shells—the top part of the shell is called a carapace—have individual sections called scutes. These scutes may have concentric rings, which give the diamondback terrapin its name. No two shells are alike.

Females lay around five to seven eggs several times a season, from April or May through July. They look for a dry, elevated spot to lay their eggs and dig a lightbulb-shaped chamber in the ground about six inches deep. They lay their eggs, cover the nest with substrate, and tamp it down with their rear limbs to disguise and camouflage the area. Some 40 to 50 days later, if everything goes right, the eggs hatch.

Unlike sea turtles, terrapins—who can live for 30 years—don’t roam far from home, moving only a few miles (at most) from where they’re born. “This can be good for conserving them,” says Davide Zailo, a research program manager at the Center, “but it can be a negative if you have issues like crabbing, pollution, or physical barriers to nesting.”

Addressing those issues is where the Georgia Sea Turtle Center steps in.

A CAUSEWAY FOR CONCERN

The 6-mile-long Jekyll Island causeway carries nearly 3.5 million people onto the island every year, but it poses a problem for female diamondback terrapins. “Similar to sea turtles, terrapins have to lay their eggs above where the tide comes in to prevent the nests from being covered by water,” Zailo says. To a nesting terrapin, then, the causeway seems like a perfect elevated surface to create a nest. Unfortunately, more than 100 females are killed each summer as they attempt to cross the causeway. “Their instinct when they are scared is to pull into their shell,” says Zailo, “which doesn’t help when a car is coming down the road at 55 mph.”

The Georgia Sea Turtle Center helps turtles avoid the dangers of the roadway through a variety of methods. The flashing signs, similar to crossing signs in school zones, are turned on during daily high tides to alert motorists. Staff members also physically monitor the causeway; the team estimates it logs about 500 live encounters with the animals per summer. Additionally, electrified elevated nest boxes are positioned along the roadway to provide safe nesting areas while attempting to stave off natural predators such as raccoons.

The Center also assists with managing the roadside vegetation to help redirect females in search of high ground. “If a terrapin comes up on one side of the road and there are tall trees on the other side of the road, there’s a higher chance they’re going to try and cross the road,” says Zailo. “We suppose that they think the trees are an indication of a higher elevation.” Fencing along the causeway to prevent the terrapins from crossing also has been helpful. “The fencing is only about 1,000 feet long, but it’s probably saved around 150 or 200 turtles over the last two seasons,” Zailo says.

(While cars on the causeway are the main threat to female diamondback terrapins, recreational crab pots spell serious trouble for males and smaller females of the species. They smell bait in the pot, become trapped, and eventually drown. “It can be devastating to the population as a whole,” says Kaylor.)

Aside from the critical task of trying to save turtles on Jekyll, the Center implements these measures to teach conservationists in other areas, too. “We’re using our causeway as a model system to help save and protect the terrapins with the hopes that these efforts can be developed by other institutions or counties along the East Coast,” Zailo says. “We want to study them, figure out solutions to their problems, and broadcast those to the world to help improve their outcomes.

“The terrapin population on Jekyll is likely one of the most studied terrapin populations in the Southeast,” Zailo adds.

BACK ON FOUR FEET

While the efforts on the causeway and elsewhere clearly have made a difference, injured and in-danger terrapins still arrive at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center every year in need of help. Visitors can observe injured turtles in rehab and check in on incubated hatchlings that are patiently raised during the colder months and released in the spring.

The work can be emotional for staff and visitors alike, especially as injured terrapins move back into the wild. “Gasket came into the hospital after being hit by a car,” Kaylor says, recalling a particular female. She was missing the right side of her shell where the top and bottom come together, along with collapsed reproductive organs and fractures. “She was very unstable. We found her on the road and brought her to the hospital where we were able to use surgical plates to secure her shell back together and stabilize it,” she explains. After months of rehab and wound management, she was released into the wild almost a year later.

Since 2007, the Center has notched more than 4,600 encounters with live, uninjured terrapins as part of its work. And though it’s difficult to pin down the exact number of terrapins that have been saved —”Terrapins are a hard species to survey methodically as they live in pretty inaccessible areas,” says Zailo—those who work with these animals are confident in the impact that the Center has had.

“Conservation is a slow effort and it can often take time to see the benefits, so it’s always exciting when it happens,” says Kaylor. “We’re starting to see our efforts pay off. We have mature females that were little hatchlings that we incubated and now they’re in the population laying eggs.”