A tale of the island’s first cottage, an eccentric millionaire hermit, and a rumored love affair

BY TONY REHAGEN

In the days following his death, as attendants cleaned the cabin where the “Hermit of Essex Coast” had spent the last half of his lonely existence, newspapers, including The New York Times, reported that “the charred remains of a photograph of a woman” was found. Even at the time, reports of the mysterious photo’s existence were in dispute—one of Brown’s stewards was quoted as saying the story was “all bunkum.” But the story fits neatly into a romantic narrative that began 38 years prior to Brown’s death, more than 4,000 miles away, across the Atlantic Ocean, on Jekyll Island. There, in 1888, a half-mile north of the Jekyll Island Clubhouse, Brown had commissioned construction of the island’s first cottage. Brown built the house, the legend goes, for himself and his bride-to-be.

But neither he, nor any lover of his, ever stepped across the house’s threshold. In fact, Brown never stepped foot on Jekyll Island at all.

“There’s no evidence to actually back up this story,” says Andrea Marroquin, curator of Mosaic, the Jekyll Island Museum. “But it’s a tale of unrequited love.”

Brown joined the Jekyll Island Club in the organization’s first year, 1886. He was 34 and had just inherited—as the sole heir—his family’s fortune. But he was still active in business, maintaining an office in New York as either a lawyer or (according to different sources) a banker. He also served as a board member for the Terminal and Danville railroad lines. Brown had a reputation as a socialite, with membership in the upper-crust Knickerbocker Club, the Union Club, and the Riding Club. He was mentioned in the gossip columns of the Times and other publications. Around this time, Brown also somewhat ironically began to show hints of an antisocial personality that would only intensify through the course of his life.

One of the early signs of his withdrawal from society may be found in his connection to Jekyll Island. At the time, the island was about as remote a getaway from the white-tie gala of gilded-age New York that a millionaire could find, while still maintaining an accustomed level of luxury. Brown paid his dues to join the ritzy Jekyll Island Club, but bucked the idea of boarding in the posh clubhouse, becoming the first Club member to build a cottage. He seemed to intentionally position it in a relatively secluded area of the island overlooking the Marshes of Glynn.

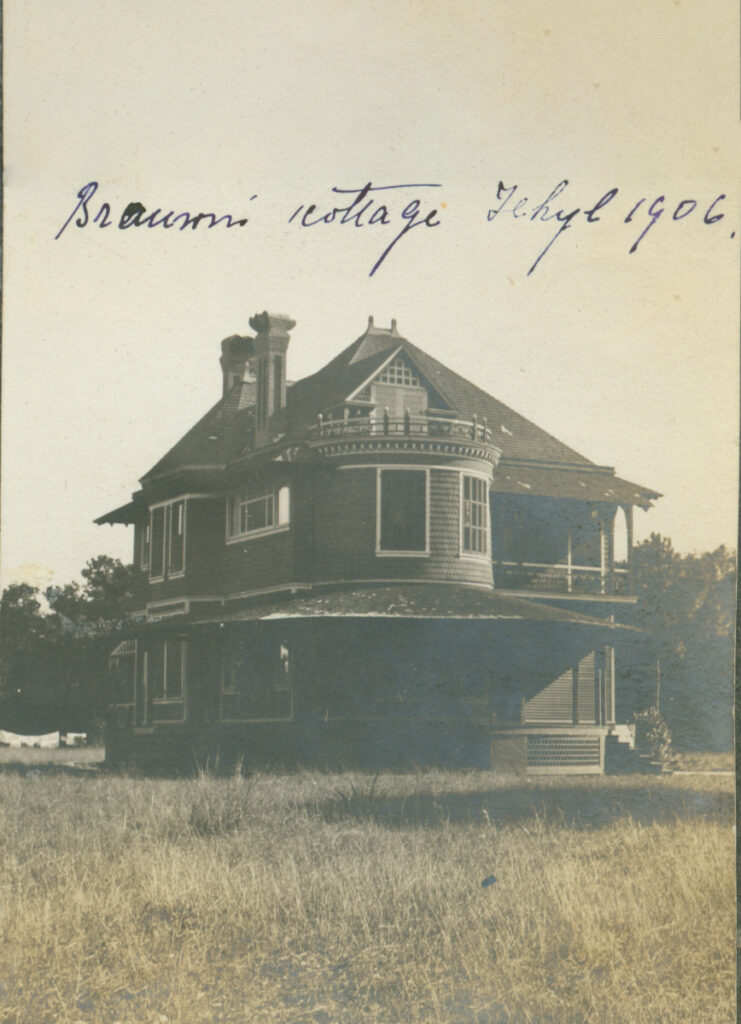

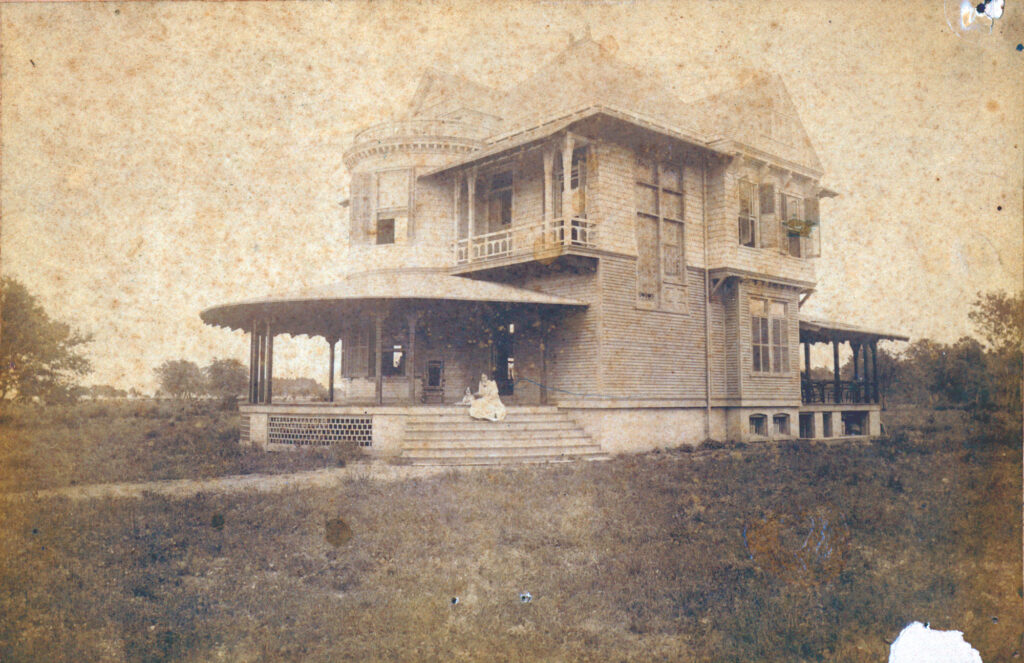

Brown Cottage was built in 1888 and valued at $10,000. Brown enlisted architect William Burnet Tuthill, who had designed Carnegie Hall, the Princeton Inn, and the Columbia Yacht Club. The Queen Anne-style cottage was somewhat humbler: Two stories with a semi-circular wraparound front porch leading to a first-floor living room, den, dining room, and pantry.

Upstairs were three bedrooms and a bathroom. The kitchen was in the basement with a servant’s dining room, an extra toilet, and a dumbwaiter. And a bridge over the marsh connected the home to the stables.

On the cottage’s facade, large bay windows in the living room and the second-floor master bedroom were distinctive. And the broad covered porches at either end of the structure would have provided ample opportunity for a loving couple to bookend their days with sunrises and sunsets.

Not that the home’s owner would ever see any of it. By the time of the house’s completion, Brown already had set sail for Europe, never to return to the U.S. “Brown would never discuss his reasons for leaving America,” says Marroquin. “He just exiled himself to his palatial yacht for 36 years. He maintained a crew of 18 men with standing orders to put out for his homeland at any moment. But that order never came.”

The absence of an explanation for Brown’s self-expatriation opens the way for alternate tales, like the story of an unspeakable, doomed love affair. Likewise, the lack of any evidence of Brown ever having any companion in his life creates a blank canvas upon which speculators can sketch a Helen of Troy.

“Nothing is known about the young woman in question [in the charred photo], and her identity remains a mystery,” writes author and professor June Hall McCash in “The Jekyll Island Cottage Colony,” a 1998 book. “Some accounts claim she jilted him at the altar; others contend they were actually married when she ran away; still others question the story altogether.”

No matter how fanciful, the story also gains credence by later accounts of Brown’s erratic behavior. As early as 1894, the New York Daily Tribune reported that his antics had “passed the border which separates eccentricity from insanity.” In Brightlingsea, the nearest Essex town, he was known to alternately throw beggars gold sovereigns or hot coals from the deck of his yacht, depending on his whims. Crewmen would report that Brown would randomly soak them with water from a giant syringe or creep up on them in bed to beat them with the cook’s poker for somehow offending him. Paranoid, he’d sometimes suspect that dynamite had been hidden among the coals onboard, so he’d have the entire load thrown overboard. And he burned all of his mail immediately after reading it, including newspapers from his native New York, which he didn’t want any of his staff reading. In fact, McCash writes, “none of his men was permitted to mention America in his presence, it was said, nor, they claimed, did he ever speak to them about his homeland.”

Back on Jekyll, Brown Cottage led a far less eventful existence. It sat vacant for some time before its upkeep was passed on to a live-in caretaker, Jekyll Island launch captain James Agnew Clark. The captain was asked to leave when, on another whim, Brown decided from England that he wanted the house refurbished. When the work was done, Clark refused to move back, in part because he deemed the cottage’s location undesirable for him and his new wife. The home’s remoteness prevented sale or even leasing of the structure, so Brown Cottage spent the remainder of its lonely time alternately housing caretakers and workers of the Club.

Reports indicate that Brown Cottage stood until the end of the Club Era in 1942. By the time the state of Georgia took control of the island in 1947, little remained. Sometime in that interim, the structure, likely crumbling, burned down or was demolished. Today, the only sign that Brown Cottage ever existed is the foundation of a brick chimney on the site near Jekyll Island Airport and a historical marker that briefly recounts the tale of a millionaire absentee owner.

In reality, the indisputable story of Brown Cottage is one of a home abandoned, not a lover. But the house’s romantic story of unrequited love, if apocryphal, endures.