Prized for its long, silky fibers, Sea Island Cotton dominated Jekyll’s economy for seven decades.

By REBECCA BURNS

In the spring of 1862, Union Army forces made their way along the coast of the Carolinas and into Georgia, moving from Skidaway to St. Simons to Jekyll. They seized plantations from their owners, who drove their enslaved workers inland to “protect” their property. In doing so, a major economic driver of the region was disrupted: Sea Island cotton.

A rarified strain of an ancient species that thrived in the muggy, muddy flatlands of the barrier islands, Sea Island cotton fueled great wealth for a small group of growers, provided trade for hundreds of merchants, created brutally inhumane work conditions for thousands of enslaved men, women, and children, and was a linchpin in the global economy for millions.

“The sea island planters are rich and proud, very aristocratic, and fiercely traitorous,” reported The New York Times on April 3, 1862. “In their expulsion and by the confiscation of their slaves, the original and worst element of secession is humiliated, if not ruined.”

Indeed, the Civil War brought an end to seven decades of an industry in the coastal Southeast that thrived due to two main factors: the region’s unique geography and its rigid reliance on slavery.

A Revolutionary Product

While the Civil War halted cotton planting on Jekyll and other coastal islands, the industry’s beginnings were forged in another pivotal conflict. “The history of Sea Island cotton on Jekyll is revolutionary—literally,” says Andrea Marroquin, curator of Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum. “The Revolutionary War brought it about.”

Before that war, Jekyll Island was owned by Clement Martin, a Brit who was said to have brought the first enslaved people to the island. After his death, the property went to his son John Martin, a Royalist, who in 1776 was listed as being “at large and a danger to liberty.” He eventually was charged with treason and banished from the United States. The government seized his Jekyll property and Martin fled, eventually relocating to the Bahamas.

When the government put the confiscated property up for auction, it was purchased by Martin’s brother-in-law, Richard Leake, who owned and operated Jekyll from 1784-1791. A few years into his tenure, Leake began growing Sea Island cotton, “presumably using seeds sent by John Martin from the Bahamas,” Marroquin notes.

Sea Island cotton met American demand for fabric when the supply from British textiles dried up during the war. Then in the post-war boom in British industrialization, demand soared for the cotton, known for its silky, lengthy fibers. As Sven Beckert notes in his acclaimed book Empire of Cotton, exports from South Carolina surged to 6.4 million pounds in 1800 from just 10,000 pounds a decade earlier.

On Jekyll, the cotton’s saga shifted thanks to another conflict. Fleeing his native France after the French Revolution, aristocratic sea captain Christophe Poulain DuBignon came to Georgia, eventually buying all of Jekyll Island and embracing life as a cotton plantation owner. In 1799, DuBignon earned $30,000 selling cotton—almost $750,000 today.

After a peak in the early 1800s, the cotton remained a viable revenue source for Jekyll and the DuBignon family, but its profitability declined. Eventually DuBignon’s son, Henry, sold the island to a group of wealthy businessmen and industrialists, and the historic Jekyll Island Club was created.

Bloody History

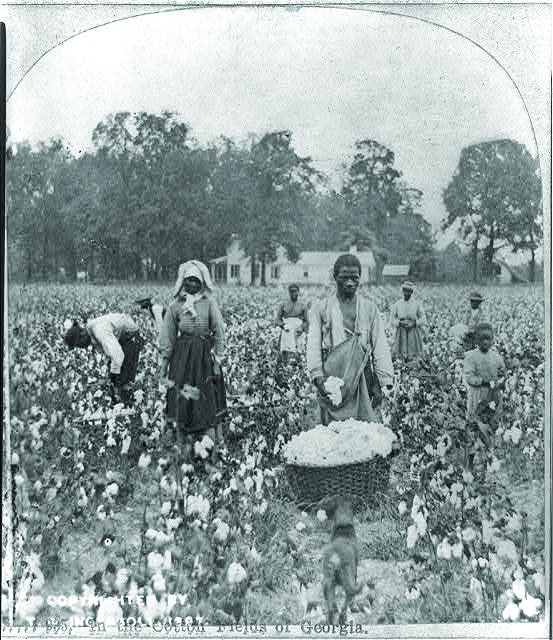

The economics of Sea Island cotton—like its inland counterpart throughout the South—were dependent on the work of enslaved people who grew, harvested, and processed the plants. On coastal plantations, the work often fell to women and children, who were believed to have a delicate touch that the long-fibered cotton required. Sea Island cotton is harvested the instant a pod opens, and as the plants produced bolls over a months-long growing period, enslaved workers were forced to make up to 10 passes through a field during each season.

Sometimes the enslaved worked by moonlight to complete a harvest cycle. Processing the cotton, including tedious ginning—removing seeds by hand—also was done by enslaved women, who often worked in the gin houses while pregnant or just days after giving birth.

“The whole process, from the picking to the packing of the cotton created a certain tenseness which everyone experienced,” writes Margaret Washington Creel in the research journal Negro History Bulletin. “A constant, driving momentum was kept up while quality work was also insisted upon to make the crop as profitable as possible.”

During the Civil War, formerly enslaved men from the coastal islands were among the first to join the Union Army, leaving even more of the cotton production work to women, who continued their efforts after the war, when the U.S. military and government took over plantation oversight.

“There was progress represented by the cotton, but we need perspective,” Marroquin says. “There is blood behind that history.”

A New Perspective

Today, a small garden at Jekyll Island’s Horton House—where the DuBignon family lived for generations—contains Sea Island cotton plants along with other historic crops such as indigo, hops, and barley. The project was conceived of and is managed by Jim McKenna, who retired to Jekyll after 35 years as a crop scientist at Virginia Tech.

“Most people wouldn’t recognize long-staple cotton if they fell into a field of it,” McKenna observes. “And indigo is, for most, a mystery wrapped in an enigma.” The demonstration garden offers visitors a chance to see and learn about the crops that played a significant role in Jekyll’s history. Hops and barley provided the ingredients for the beer brewed by William Horton, the home’s original occupant. Indigo was exported throughout the colonial period. And Sea Island cotton was a valuable crop that drove much of the economy on Jekyll and throughout the region.

“Long-staple cotton thrived on the Georgia and South Carolina islands, thanks to the salt in the air and the 300-plus day growing season,” explains McKenna. The fields were enriched with marsh mud, an ideal compost for the cotton plants, which grew as perennials on the sea islands.

McKenna, assisted in the garden by his next door neighbor, retired biologist Al Tate, says that growing these plants now offers a way of understanding the agrarian history of both Georgia and the United States as a whole. And it provides a new perspective for visitors to Jekyll, who have long enjoyed the preserved artifacts and historic structures on the island. Now, through these plants, they can partake in a living history lesson as well.

An Ancient Taxonomy

Exactly how cotton seeds got to the coastal Southeast remains a matter of conjecture, but thanks to the science of systematics, researchers now know more about Gossipyium barbadense L., the species that includes all long-staple cottons. According to The Story of Sea Island Cotton, researchers traced and confirmed that G. barbadense originated more than a million years ago in Ecuador and Peru. It then made its way to the Caribbean and eventually to Georgia.

With the cotton industry failing after the Civil War, Sea Island seeds were sent to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Pee Dee Experimental Station in the early 1900s. From there, they were distributed in South Carolina and Georgia in 1934 in an effort to bring back the industry. The attempt failed and the seeds were not saved. “The last seeds having been lost, Sea Island cotton as grown on the Carolina sea islands is gone forever,” writes botanist Richard Dwight Porcher in The Story of Sea Island Cotton.

Today, only one percent of the cotton seeds in the world are long-staple cotton, says Jim McKenna, the retired crop scientist who coordinates the demonstration garden at Horton House.

Jekyll’s cotton plants have been grown from seeds ordered online, and cultivated using techniques that mirror historic growing methods. In 2022, seeds were saved from the Jekyll crop and planted for the 2023 season. “We could become a Sea Island cotton seed source here on Jekyll,” McKenna notes.