Before The Allman Brothers Band hit the big time, there was a high school dance on Jekyll…

BY SCOTT FREEMAN

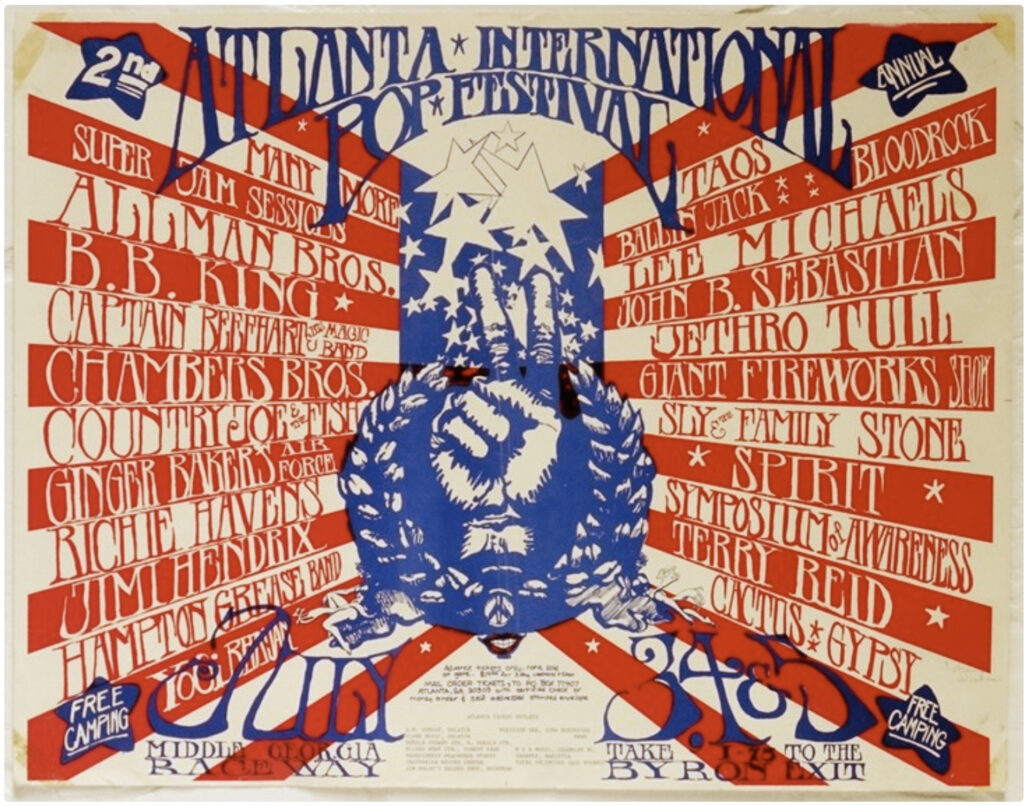

On Friday, July 3, 1970, the Allman Brothers Band opened the three-day Atlanta Pop Festival at the Middle Georgia Raceway in Byron, taking the stage around 7 p.m. An estimated 300,000 people were packed together in the blazing Georgia heat, drawn to the Southern version of Woodstock and to hear headliners Jimi Hendrix, Procol Harum, 10 Years After, Mountain, Richie Havens, and B.B. King. Few in the audience were there specifically to see the Allman Brothers, and most didn’t even know who they were. The band had underground followings from performances at fledgling rock concert venues in New York City, San Francisco, New Orleans, and Boston. And the Allmans had built a strong fan base in Atlanta through a series of free Sunday afternoon concerts in Piedmont Park. But a band that would grow into one of rock’s most legendary groups was still largely unknown to the masses and scrambling just to survive.

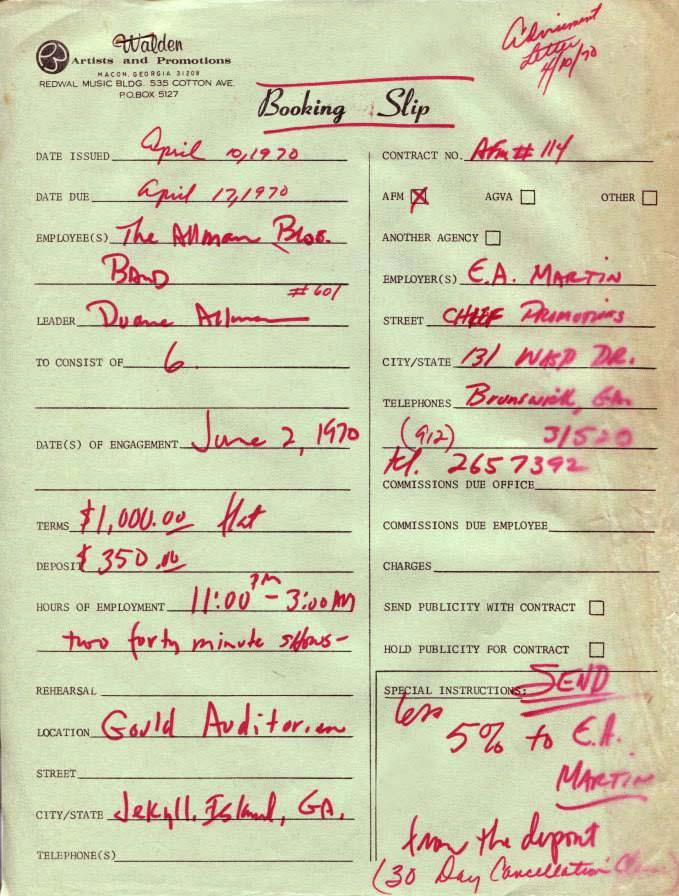

In fact, four weeks before the Atlanta Pop Festival, the Allman Brothers Band had played one of its more profitable shows of the first half of 1970; a party for the Glynn Academy senior class at Jekyll Island’s Gould Auditorium. (Glynn Academy, one of the oldest high schools in the nation, is a public school in nearby Brunswick, Georgia.)

“June 2, 1970 at Gould Auditorium, that was my first gig as their road manager,” says William “Willie” Perkins, who became one of the group’s longtime mainstays. “We made a thousand dollars, which was big at that point. High schools, fraternities, colleges, we hit them up pretty good. Back then, we averaged around five or six hundred dollars a night for most shows.”

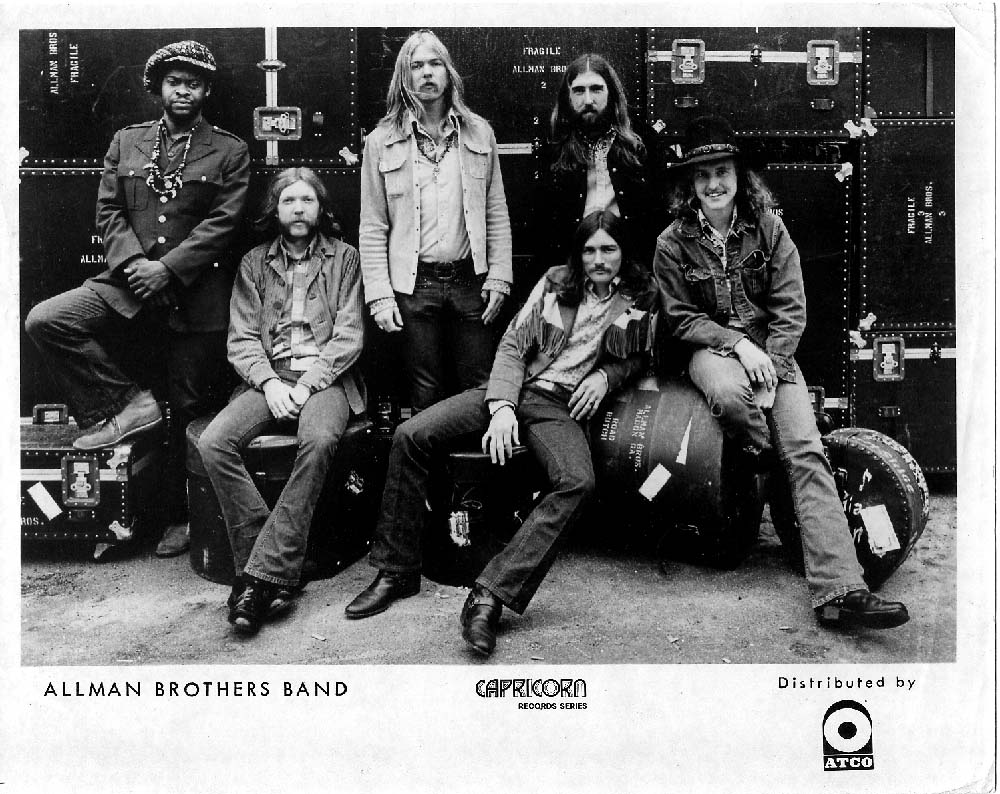

Courtesy of The Big House Museum, Macon, GA

Booking slip courtesy of Willie Perkins

The Gould Auditorium show, for the few who witnessed it, showcased a band on the cusp of breaking through.

Duane Allman and his little brother, Gregg, were born in Nashville but spent most of their childhood in Daytona Beach. The two brothers first gained a musical following in northeast Florida in the mid-’60s with their band the Allman Joys. Duane and Gregg were teenagers when the band started, musicians with blazing talent but still working to hone their skills.

Bob Herrin, who would become the guitarist in Flood—a band based out of St. Simons Island—had a friend in Daytona who told him, “You’ve got to hear these guys.” So Herrin drove to Daytona one weekend and was blown away by both brothers: Duane’s command of the guitar and the power of Gregg’s voice. “I heard them play on the pier in Daytona, and then in a little club,” he says.

In March 1969, Duane and Gregg joined forces with four other musicians in Jacksonville to form the Allman Brothers Band. The band had two drummers, one of whom was Black, making the Allman Brothers the first interracial rock band from the South. The musicians moved to the sleepy city of Macon, where their manager, Phil Walden, was based. Walden guided the career of Otis Redding until the soul singer’s death in a 1967 plane crash, and had shifted his focus to the world of rock and roll.

The Allman Brothers Band debut album—which featured such signature songs as “Whipping Post” and “Dreams”— was released that November and had gone largely unnoticed, initially selling just 34,000 copies. With concert venues and rock clubs few and far between in the Southeast, the band regularly played college fraternities and even high school dances during its hardscrabble early days.

When Glynn Academy senior Robert Anderson became aware that the Allmans played high school gigs, he was determined to book them for the academy’s senior night party. Like Herrin, Anderson had seen the Allman Joys in Daytona and Gainesville, and was a huge fan of the Allman Brothers Band. He and the senior class president happened to be in charge of the school’s senior bash, where a party band called Leaves of Grass was scheduled to play.

“The class president and I absconded with the funds for the senior party, ditched the sanctioned party band in favor of our last minute hire, the Allman Brothers Band,” Anderson wrote in a Facebook post. “The football dudes wanted to murder us for shucking Leaves of Grass, a favorite of senior parties of the past, and moms and chaperones everywhere.”

Herrin and members of Flood came over from St. Simons Island to see the Allman Brothers perform at Gould Auditorium. “We hung out with them outside the back door where they loaded in their gear,” he says. “Gregg was doing a lot of drinking that night. We actually helped carry him onstage to his B-3 organ.”

The members of Flood were among the few people outside Glynn Academy who witnessed the show. “There weren’t a lot of people. It was a senior party,” Herrin says.

For the uninitiated seniors, it must have been a culture shock when they heard the Allman Brothers Band fire up. There was no beach music to be heard, no familiar Beatles or Motown covers; this was hard core blues-based rock played at extremely high volume.

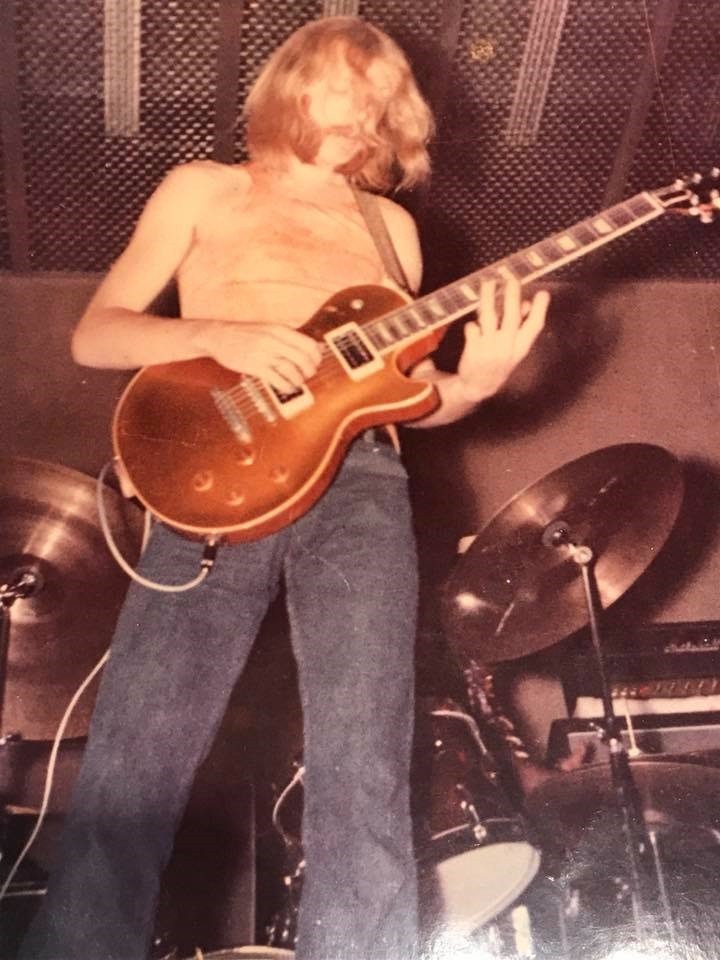

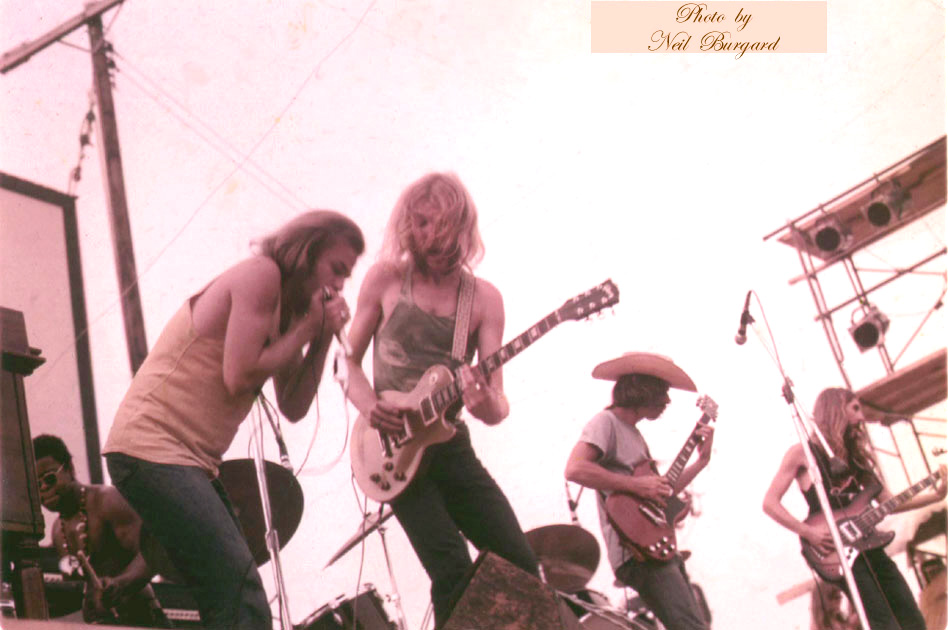

On stage at Gould—Duane Allman plays his famous Gibson Les Paul Goldtop, which recently sold for $1.2 million. Photo by Merle Tory Torstenson

“It was a great concert,” says Herrin. “I was surprised at how good they sounded. I was impressed with ‘Dreams’ and Duane’s sweet slide playing. I remember they did ‘In Memory of Elizabeth Reed’ and ‘Whipping Post,’ but I don’t remember what else they played.”

In his Facebook post, Anderson said bassist Berry Oakley wore a Confederate soldier’s cap. “They looked like Confederate generals risen from the dead to redeem themselves for slavery and the century of Southern oppression that followed. ‘Whipping Post’ struck me as existentially poignant. It was cathartic.”

Three weeks later, Herrin and the members of Flood drove to Byron ahead of the Atlanta Pop Festival to try to talk their way onto the bill. There was a “free stage” set aside for local bands and for jam sessions, and Flood essentially took over there as the resident band.

In 1971, as the Allman Brothers had done at Piedmont Park, Flood set up one afternoon at the south end of Jekyll in the picnic area and played for free. “We had no permits, and we had a bunch of college kids show up,” says Herrin. “We did it again in 1972. A couple of promoters got involved and all of a sudden, they were expecting 10,000 people. It really got out of hand and we didn’t do it again after that.”

Flood later signed a record deal and performed a big show at Jekyll’s now-dormant amphitheater. Despite a critically lauded album, stardom didn’t come for Flood.

These days, three of the original members, including Herrin, perform as Tie Dye Sunset around the Golden Isles. For the Allman Brothers, the Atlanta Pop Festival served as a springboard for the group to begin to take its place as one of the great American rock bands.

The Allmans opened the festival Friday night, then closed it early Monday morning. They played with muscle and finesse, and were the clear hit of the festival. The unreleased film of their performances is electrifying. The festival was a coming of age for the group, and the place where the Southern rock movement began to take root. In the last months of 1970, the band’s popularity surged and a second album was released. Gigs at frat parties and high school dances were no longer necessary.

In fact, Perkins says, it’s likely Gould Auditorium has a singular distinction: the site of the last high school dance the Allman Brothers Band ever played.

About Gould Auditorium

Gould Auditorium was built in 1913 by Edwin Gould as a casino for members and guests of the Jekyll Island Club. In 1957, the structure was remodeled and converted into the Gould Auditorium. It served as the island’s first convention center. It also played host to high school dances.

Scott Freeman is the author of Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band. He is the executive editor of ArtsATL.